Don't Give Your Money to Operation Underground Railroad, Part 2

Raid and rescue and its limitations

In the last article we challenged three claims that OUR has historically made about itself or that others have made on its behalf: that 1) OUR was started because a nonprofit could do more to effectively combat human trafficking than government agents could, that 2) OUR has never found Gardy Mardy, but every effort it makes looking for him rescues more kids, and 3) The more donations OUR gets, the more operations it can stage, and the more kids it can save.

In this section, we’ve got three more claims to look at. I strongly recommend reading part 1 first, especially if you want to know where all the Powerpoint images came from.

Claim 4: OUR is effective at freeing children from trafficking and providing them with necessary aftercare.

It’s not always clear what exactly OUR adds to a raid. It’s certainly acceptable that OUR works with a variety of governmental and non-governmental organizations to perform its work. For example, Operation Triple Take in 2014 (depicted in the movie Sound of Freedom) was a collaborative project involving ICE, HSI, the Colombian navy and coast guard, and the nonprofits Operation Underground Railroad and Breaking Chains. This isn’t wrong, of course, and it’s maybe even advisable for nonprofits to collaborate with officials on legal and criminal matters. But as donors consider whether to give to OUR, the involvement of other orgs in OUR operations seems to be information to consider. For instance, Ballard has argued for OUR’s importance on the grounds that “no one” besides his group is trying to stop trafficking. This is clearly not true. There’s also the question of what OUR adds to an operation in their capacity as assistants.

On this front, the news is mixed. Steven Cass, founder of Breaking Chains, OUR operative and DHS agent, says that most of the work in early OUR takedowns (2014-15) was actually completed by him. As he puts it, the operatives flew in for sting day, but Cass completed prosecutable intel before they even arrived. In fact, Cass maintains that OUR arriving with cameras, volunteers, and donors actually scrambled work that could have been done better without them. Because the media wing of OUR has historically been so central to its operations, it seems that they’ve sometimes vulnerable to emphasizing film and television production over effective work.

This is particularly pronounced in an incident that’s depicted in the TV show The Abolitionists.

During raids in Acapulco and Boca Chica (eps 2 and 3), Ballard and his associates are posing as possible johns seeking sex with children. When interacting with pimps, they continuously press them for more and younger children, and are stymied at one point in the footage in which a pimp brings them a bunch of twenty-something women he is trying to pass off as minors. The group is repeatedly frustrated when they realize that the johns are bringing them sixteen year olds and trying to insist they are younger, or when they promise they can bring more kids than they actually do. In Acapulco, a trafficker promises to bring them young children, but is disappointed when they appear to be older teenagers.

What’s the logic of this? If the goal is simply to push back on trafficking of children overseen by adult managers, then the pimps can be arrested whether they bring two kids or forty. It seems to me that there are two issues here. The first is, as we have said in other articles, possible “cabal goggles” – OUR is working with the assumption that “trafficking” happens when a pimp has a warehouse full of kids somewhere, and so the pimps need to get as many people out of the warehouse as possible and needs to be pressured to clearing it out for the raid. This is, first and foremost, not how trafficking works. The pimps likely don’t just have a bunch of kids somewhere, they go lean on sex workers they know or manage to find young acquaintances who they can conscript. But more importantly, the logic doesn’t work. If Mario has fifteen kids in a box, and Mario is arrested when he is caught with one of them, the raid on his property will presumably reveal the other fourteen whether he brought them to the fake johns or not.

I think the better explanation is actually that they’re looking for better and better footage. Walking twenty nine year olds out of a party is going to look much more dramatic than five girls who are indistinguishable from adults. If the goal is to get people who sell sex with minors off the streets, there’s no reason why the operatives need to specifically catch these men selling a lot of very small children. But the reason does present itself if all these needs to be pitched for network television.

This brings me to the subject of aftercare. In the raid-rescue-rehab model of trafficking intervention, rescue and rehab are two completely different steps – women and children are whisked away from brothels where they are being exploited, and then are put in programs where they are sheltered, counseled, and sometimes given job training. As we’ve said, this is a system that is derived from the assumption that women are being held against their wills and would return to normal life given the option. The reality is that this system is often disruptive and traumatizing for women, and doesn’t solve the issues that cause women and children to enter exploitative sex work in the first place.

This shows up again and again in OUR history. In an episode of The Abolitionists, during a raid in the Dominican Republic, OUR stumbles upon a young woman who they had actually rescued the year before and was now back in a brothel. They offer her the chance to come with them and start aftercare again, but she turns them down. After a raid in Boca Chica, Meg Conley later discovered that every child who was “rescued” in this operation was released from the institution where they were held a week later.

In a third incident in Haiti in Aug 2020, OUR publicized an incident in which they took what they described as sex trafficking victims to the US for job training and citizenship in the US.1 (If you’ve ever seen Ballard hold up a padlock saying that it was the very lock that kept them imprisoned, this is that story. As Lynn notes, the role of the lock in the brothel is not clear and doesn’t seem to be in living quarters, and most of the dramatic chase that Ballard describes is contradicted by extent footage).

In this operation, OUR encountered a group of women in Haiti who were originally from Venezuela and Colombia who were having some kind of dispute about passports and money owed with their pimps. This can meet the definition of trafficking; however, as Laura Augustin notes, this arrangements can sometimes be more complex than meets the eye. I am not taking a stand for or against this arrangement; I am simply acknowledging that sociologists document a lot of ambiguity in these situations, and as far as I am concerned, the fact that the women wanted to leave the brothel is all the information that concerns me. OUR arranged for the women to get visas using Ballard’s political connections and, instead of returning them to South America, flew them to the US. They then went to the White House to meet former President Trump (there’s no footage of this in the documentary). Ten of the thirteen women were then taken to Utah State for an extension course taught by graduate students and a staged graduation ceremony. We don’t know what happened to the other three. Of the ten, three are in South America, and seven are in the United States.

Is this actually successful aftercare? As Lynn notes, the story that the women themselves tell about how they got to Haiti in the first place is not the same one that OUR tells. OUR says the women were drugged, kidnapped, and smuggled from Colombia to Haiti, but two of the women who have told their stories on tape say that they went to Haiti with the goal of making money, and say they did not know that sex work would be involved until they got there (or possibly regretted their choice once they were in debt in Haiti – the language they use is not incredibly clear. Most interviews with women who were at the brothel make it clear they expected to do sex work, so it may be that the unpleasant surprise that arrived in Haiti was related to the financial arrangement there). Other scholars of sex work in the global south have argued that in these situations, women may misrepresent their stories when talking to police aid workers to avoid prosecution for sex work, prevent deportation, or to receive assistance from wealthy aid organizations intent on helping them. I am not saying this makes the women not victims or liars – merely that poverty creates a lot of complicated incentives for immigration and dealing with officials who are usually not kind to sex workers. Of the original thirteen women, six are now outside of OUR care. What mechanisms exist to prevent them from returning to sex work of dubious safety and agency is not at all clear. News stories about the brothel written before the raid recount that women came there from Venezuela to work and told reporters that with the money they were able to buy medicine, houses, food, and school fees for their families back home. Who in Venezuela is offering a more attractive deal?

As for the other seven, OUR says that they live in the US. Their future here is not any clearer. Immigration lawyers have challenged the claim that the women are on their way to US citizenship on the grounds that no clear path to citizenship exists for people who receive T visas (visas that are reserved for survivors of trafficking). It’s still a slow process. It’s also not clear what meaningful economic opportunities exist for South American immigrants who have taken an extension course at Utah State, even in the US. It’s not hard to imagine how they could end up tied to OUR for years, both for financial support and protection of their status as legal residents. As Anne Elizabeth Moore notes, “rescue” is not really possible without true poverty elimination. My point is not that the women should not have been allowed to leave the brothel – surely not. My question is whether this system of bringing them to the US to work on visas is 1) a scalable solution and 2) whether this provides agency and independence that women need – especially with the US’s stringent immigration policies.

The irony of this is that when Matt Osborn with OUR tells the story, he recounts that the Haitian pimp did not imprison the women and told them they were free to leave if they didn’t like the arrangement – the women were simply not able to because they were in debt, didn’t speak the language, and didn’t have anywhere else to go. If aftercare creates the same limitations as sex work did in the first place, is this actually effective? These are serious concerns that other, smarter people than me who work on this problem have raised.

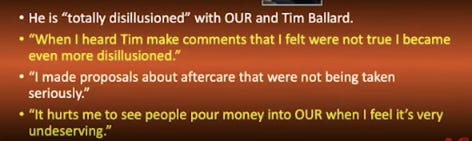

The problems of OUR aftercare came out in Lynn Packer’s interview with Ed Smart. Ed Smart served for two years as the director of aftercare at OUR and eventually split with the organization because of his frustration with the program.

In conclusion, the success of OUR aftercare, and therefore the success of any of its rescues, is hard to gauge. Organizations that do aftercare do not want to confirm or deny that anyone rescued by OUR is in their care, largely because of the highly publicized nature of OUR footage and the desire to not endanger people. OUR has historically insisted they can’t provide data about aftercare on the grounds that it would endanger people who are receiving it. However, they are more than happy to brag about the fact that it happens, despite the fact that evidence on the ground is not always so clear.

Claim 5: The prevalence of trafficking means we shouldn’t question organizations that are trying to fight it.

So this claim has two parts: trafficking is too big of a problem for organizations fighting it to face criticism, and no one who is even attempting to solve this sprawling problem that no government takes seriously should be challenged.

We’ve already challenged the idea that OUR and similar NGOs stand alone in fighting trafficking. This is clearly a problem that receives a lot of time, attention, and money from the US government and the UN, just to name two obvious entities. So it’s hardly possible to say that

OUR has historically been fond of large pronouncements involving large numbers about the scale of human trafficking, the scale of trafficking in the US, the money involved in trafficking, and the rate at which trafficking is growing. OUR and affiliates like Utah AG Sean Reyes emphasize the prevalence of trafficking using numbers that are widely rejected by reputable organizations – that it is the fastest growing criminal enterprise in the world, that every 30 seconds a child is stolen for sex or organs, that two to five million children are trafficked for sex every year, and that 10,000 children are smuggled into the US annually for sex. Sean Reyes has even claimed that many women are kidnapped for trafficking from Utah.

In reality, the claim that trafficking is the “fastest growing” criminal enterprise on earth is a riff on a claim from a 2010 International Labour Organization report, that calls it “one of the the fastest.” As we have argued, prevalence data for all kinds of trafficking are incredibly difficult to find, and most reputable organizations will not make claims about frequency. Incidents of children being smuggled into the US for sex trafficking are incredibly difficult to find. These are numbers that are, on the whole, not supported by other experts in the field.

As we have discussed extensively, other anti trafficking organizations do not subscribe to prevalence data that OUR uses, and in fact have recently distanced themselves from prevalence data at all. And, as we have also exhaustively discussed, kidnapping is actually not how most people end up in trafficking situations – poverty, marginalization, and migration are.

CEO of Rapha House in Haiti, Stephanie Freed, calls the emphasis on kidnapping “one of the biggest misconceptions” about trafficking in the US.

So, if your reluctance to challenge the methods of OUR or the person of Tim Ballard is that you don’t want to be part of the problem of millions of people being kidnapped and sold for sex, your grasp on the problem might not be as complete as you think. Insistence on the frequency of trafficking, and specifically on a narrative that is confluent with “stranger danger” fears in the US, is itself a marketing tool that organizations use to whip up devotion and collect donations. The reality is that the scale of trafficking is incredibly difficult to gauge, child sex trafficking is only a small part of the problem, and systematic poverty alleviation is really the only means we have to successfully fight it.

Now, you might be saying that it’s better to try to do something about trafficking than not do anything at all, and this is why you think anti trafficking organizations should not be challenged. But this is also a misconception. Organizations can and do harm when they operate with incomplete awareness of the society they work in. An obvious example of this is orphanages, which we’ve raised in past articles. Another recent example of this is that International Justice Mission came under fire this summer when its incentive system for “rescuing” kids led to kids who were absolutely not being trafficked getting taken from their homes to meet quotas.

OUR is not exempt from this problem. We’ve talked at length about the incident in which OUR operatives with trucks and cameras almost walked into a massacre after terrifying and angering locals at the Haiti-DR border (at the urging of psychic Janet Russon). What caused the incident was a series of rumors, one of which was that the incredibly well-equipped camera team was there looking for natural resources, and locals wanted them out. If locals were afraid that OUR was there looking for minerals, they had good reason to be terrified. Mines on the DR-Haiti border, founded by western investors, have caused environmental catastrophes, diverting water and resources from local populations. If OUR went there without doing their homework (and it seems they didn’t, since this was all led by a psychic looking for a labor camp), it’s not hard to see how they could stumble into a controversy that was top of mind for the local people that they knew nothing about. If Haitian locals had actually killed wealthy American OUR operatives, what would have happened to them? This could have seriously endangered Haitian lives in addition to the Americans – all for an operation that, I cannot emphasize enough, rescued no child slaves.

Cooperation with local police and government leaders is also risky business. OUR operative has said many times to giving money and weapons to Haitian politicians and government leaders – this equipment and weapons training was part of their early operations in Haiti. OUR associate Cass reports that OUR regularly “funded” police who agreed to work with them, on the grounds that they had low salaries. But if funding the police in the US is already fraught, funding them abroad is even more complicated. Haitian police have been accused of staggering incidents of civilian violence. If part of OUR’s strategy to fight trafficking in Haiti has been to equip and train Haitian SWAT teams, can OUR really know that it hasn’t assisted in brutal government crackdowns against political opponents and slums?

OUR affiliate and attorney general Sean Reyes actually brought OUR-affiliated Haitians to Utah for public honor. These included Haitian AG Clame Ocnam Dameus, who has been accused of a series of crimes related to corruption. If US donors and organizations are lending credibility to politicians in Haiti, are they confident they have enough insight into Haitian politics to know they’re making good choices?

This is even before we get to the problem of arresting people through Haiti’s penal system. Haitian citizens do not enjoy a reliable right to representation or a speedy trial, and Haitian prisoners are subject to torture, starvation, and even murder. As we’ve discussed in previous work, OUR arranged a sting on orphanage operator Yvrose Dalegrand on the grounds that she was a child trafficker, but the footage reveals that it seems much more likely she was arranging off the books adoptions – not that on-the-books Haitians adoptions are significantly less corrupt. Did Yvrose really deserve to be starved and tortured for this? Did OUR consider the dangers of Haitian prisons before arranging this sting – even after they had confirmed that kidnapped child Gardy Mardy was clearly not in Yvrose’s orphanage?

Claim 6: The people behind OUR are heroes.

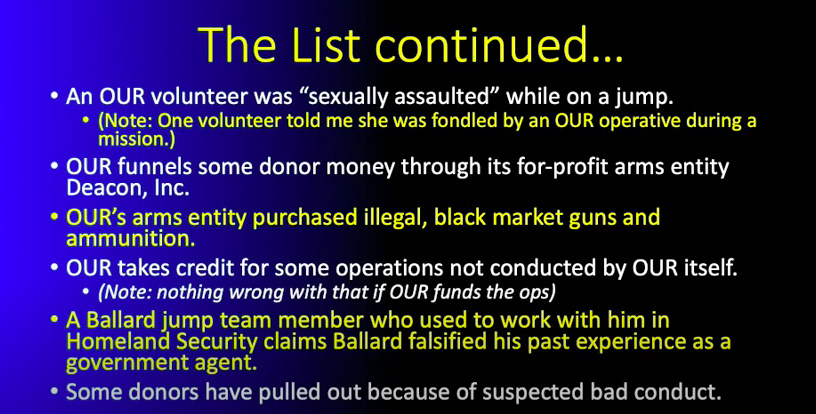

This is where we’re going to get into some material that, to be fair, I cannot independently verify. OUR has a lot of former employees, volunteers, and affiliates who have made allegations against OUR team members and supporters. Most of these people are not willing to speak on record for reasons that are, frankly, understandable. OUR, and Ballard, have a lot of money, and journalists who have investigated them have reported receiving cease and desist letters from megapowered law firms like Kirton McConkie.

On September 17, 2023, Lynn Packer broke the story that Tim Ballard had been forced out of the organization he founded after multiple allegations of sexual harassment, frequently surrounding incidents where he had women pretend to be his wives on raids. Vice released a similar story the next day.

Did Tim do it? I don’t know. But they’re not the first stories that have dropped along these lines.

These may be the complaints of disgruntled former employees. But they may not. Lynn Packer’s list of allegations he has received from anonymous people who report being afraid of being sued is extensive. I can only repeat what he has heard, which he has also heavily conditioned with the awareness that this information is difficult to verify.

As I said, I can’t verify these. Lynn has conducted interviews with some people who have both made these accusations and had accusations made against them. I can’t say what really happened.

What I can say, though, is that even without these allegations, most of what I’ve discussed above doesn’t look heroic to me. Heroes tell the truth. Heroes are accountable. Heroes respect their supporters by responsibly using funds for the ends for which they were acquired. Heroes don’t seek accolades and attention. Heroes don’t exaggerate their exploits to make them sound more exciting than they are. If all OUR says and does comes from this place of heroism and self sacrifice, why all the emphasis on film production? Why has it historically been so important to elevate their founder to celebrity status? Why haven’t they been more transparent about their operations and finances? If they really have so many heroic stories of saving women and children, why do the stories they tell never add up? Why not tell the true stories?

In a text to a third party Darrin Fletcher, producer of The Abolitionists, called Ballard “the very best liar I have ever met… whatever brings in more donors… that’s it. The ethics go right out the window for him.”

The love of money, and of fame, and of glory, of attention, of celebrity – this is the root of all kinds of evil. What it rarely is is the root of all kinds of goodness.

There are a lot of tough lessons to be learned here. We could talk about believing charismatic leaders, about the corrupting power of fame and money, about the Christian desire to believe the best about people who tell us they are the best – but ultimately, what I think we should mostly learn about this is the way Americans engage the majority world.

I think it’s easy to think, or to want to believe, that the rest of the world is a wasteland that Americans with good intentions can simply repair with good intentions and pure motives. That’s not true. Even if Ballard had been forthcoming and honest from the beginning, the dream of a show where American operatives operate as a lawless team that snatches up kids and defeats pedophiles is one that emerges from an imagining of the world where we as Americans know what other countries need, that other people don’t know how to solve their own problems, and that we can operate with only good intentions and the will to act however we see fit in other places.

This is a classic “white savior” myth. It’s not true. We don’t always know best.

I am hopeful that OUR can move forwards in more productive ways without Tim Ballard at the helm, but their model of raid and rescue, and funding police surveillance, is fundamentally flawed. In my next section I want to talk a little more about a more constructive approach to take with these issues – ones that are led by survivors and people who are actually familiar with - by birth or by immigration or by extensive, humble collaboration with locals - the issues they’re trying to combat.

I want to acknowledge that some of the language that Lynn uses for sex workers and sex work in essays discussing this incident is outdated. However, I want to flag this research because Lynn does catch the complexities of “sex work” versus “trafficking” that often emerge overseas. I’m willing to be charitable concerning the use of words and value judgments I would not use, because Lynn and I come from completely different professional backgrounds and I am nearly fifty years younger than he is. However, if you would appreciate a self-consciously feminist read of this phenomenon, see the blog Naked Anthropologist by Laura Agustin and her book Sex at the Margins.

so cool!

Thanks for exposing OUR and Ballard. I hate how in the film they have this "savior complex", but the worst part and one of the biggest inconsistencies of the film related to this is that one of the characters; Vampiro is deemed a "hero" because he buys the children and then releases them, when in fact what he is only doing is fueling the demand for children making the problem worse. I just wanted to point out even more suspicious data related to this. Eduardo Verastegui, one of the main producers and actors of the film, recently announced his intention to run as a candidate in the presidential elections of my country(Mexico) that will take place next year https://mexico.as.com/tikitakas/quien-es-eduardo-verastegui-actor-que-se-registro-como-aspirante-independiente-a-la-presidencia-n/ and if you check his recent tweets he is trying to gather more support, of course using the film.