Prologue: Who’s Lynn Packer?

My husband and I both work from home; my office is upstairs, and his is downstairs. Some time ago I was upstairs working my actual job when he yelled up the stairs at me (our primary method of communication), “HONEY, DO YOU KNOW WHO LYNN PACKER IS?”

I actually did know who Lynn Packer was, because I had stumbled across his work when I tumbled head over ass into an utterly shocking and excruciatingly grim retread of the true story behind the movie Sound of Freedom – the kidnapping of toddler Gardy Mardy from his church in Haiti, who has never been found. Lynn Packer had done extensive, exhaustive work on Gardy’s kidnapping as well as the crimes of Earl Buchanan, which I drew on in my series. What I didn’t know at the time was that Lynn Packer was the nephew of late LDS apostle Boyd Packer, that he had broken the story of the frauds of Mormon General Authority Paul H. Dunn, that a tremendous amount of his career had been devoted to investigating fraud and corruption in Utah and the LDS church, and that he’d been investigating Operation Underground Railroad (hereafter OUR) for, I dunno, maybe eight years.

So yeah, I kinda knew who Lynn Packer was.

“YEAH,” I said. “WHY?”

“BECAUSE HE EMAILED ME AND WANTS TO TALK TO YOU.”

Well, in that case.

I don’t know how Lynn was able to find Jon’s contact but not mine. (Jon’s last name is rarer, I suspect). I called Lynn on the phone and we talked about the work we’d each done independently on OUR and the stories that would eventually make their way in some nigh-unrecognizable form in Sound of Freedom. He linked his Youtube video collection, and after hours of watching this material, my initial evaluation of Lynn Packerwas more than confirmed. Namely, this is a man who knows how to show his work. I also pulled some podcasts with him and got the distinct impression that in Mormon and post-Mormon circles, Lynn’s actually not an obscure figure. To Mormons he is actually very well-known and admired (the word “legendary” shows up a lot when people talk about him).

And it’s that last part that really interests me. It’s no secret that American religious communities are incredibly siloed. We all have our own authorities, or own celebrities, and our shared cultural memories. A lot of people and properties that were indelible to my childhood would be utterly foreign to people who grew up Episcopalian, Jewish, or Muslim, even if we all grew up in the Indianapolis area. I get the impression Mormonism is very much the same way.

But this is a problem in the case of investigating something like OUR, or Tim Ballard. OUR may be an organization with a high concentration of Mormons at the helm, but its donor and fan base are by no means limited to Mormons. Sound of Freedom has brought OUR to a much more mainstream audience. Temperature-taking around my writing suggests that American Christians beyond the Mormon world have embraced the story OUR tells about itself. When I write about them, Americans across the religious spectrum tell me that it’s suspicious to even question Tim Ballard – that his heroism is so obvious, and his organization is so noble, that anyone who would even dare to look more closely or critically at it is surely revealing themselves as fundamentally evil.

But a retired veteran journalist in Utah – still quietly plugging away at his laptop with a stack of documents the size of my house – could have told them otherwise. If they’d heard of him.

So this is what I’m doing. You might not know who Lynn Packer is, but if you’re interested in OUR, you probably ought to hear some of his work. The most intense, thorough investigative work I have seen done on OUR has been written, shared, and acknowledged in Mormon, post-Mormon, and ex-Mormon circles. For a mainstream Christian audience, though, Mormon media may as well be in Fiji. We need someone to bring it over to us. What I want to do in these blog entries is to bring some of this information into American evangelical, post-evangelical, and Protestant spaces where I hang out, and make it available for my own audience.

This is not an exhaustive overview of Lynn Packer’s investigation of OUR. His investigation takes the form of a series of 29 hour-long Powerpoints, plus a stack of articles. Trying to follow along at home will make you feel like you’re tracking the Zodiac killer. A lot of the material is also probably of mixed interest to people who don’t live in Utah or don’t worship at Mormon churches – for instance, there’s some deep dives into Utah’s attorney general Sean Reyes, and OUR’s connections with Mormon pseudohistory and other extremist elements. I’m not discouraging anyone from watching, but non-Mormons will likely be puzzled, as I was. Lynn also clearly enjoys spending a lot of time establishing, for lack of a better word, the “local color” of these individuals – their family and friends, their associates, the way they talk and act, the way they spend their money. This is interesting and frequently hilarious material (Lynn is clearly entertained by AG Sean Reyes’ bad rapping). But I’m excluding this material because I’m trying to keep the focus on OUR and whether we ought to support them. It’s possible for a terrible rapper to be effective at fighting human trafficking. It just so happens that this particular bad rapper doesn’t.

I’m going to take the work that Lynn Packer has done and present the parts that I find the most compelling, the best sourced and the most meaningful to a general Christian audience: namely, material pertaining to OUR’s finances, conduct in the field, and claims about their efficacy. I started writing about Sound of Freedom a month ago, at which time I was reluctant to think about OUR’s work in terms of dishonesty, fame-seeking, and greed. After a month at this, I don’t feel nearly as reluctant.

It’s not my job as a writer to tell you what to think. But I can tell you what I think. I don’t think OUR deserves your money. I don’t think it’s demonstrated it is effective at what it claims to do. I think the people who run OUR do not understand trafficking enough to do anything about it and demonstrate minimal interest in overcoming their ignorance. I think OUR has historically replaced public trust and accountability with presenting its founder as an untouchable superhero. This strategy appears to be good for fundraising and for making Tim Ballard rich and famous. What it does not seem to be good for is ending child trafficking.

In the rest of this series, I’m going to challenge six claims about OUR I’ve heard made on its behalf, or occasionally, from people at OUR itself. We’ll cover three in this series, and then three more in the next. In the final part I’ll incorporate some interviews I’ve done with people who have worked in the majority world and, better yet, are from there, and how they approach anti-trafficking work and alternatives to the “raid and rescue” model.

A lot of the work I’m presenting here involves the figure of Tim Ballard, founder and former CEO of OUR. He has since stepped down from his position immediately following the release of the movie Sound of Freedom. It is possible that this organization can, going forward, reinvent itself without the problems that Ballard baked into this program from the beginning. But we’ll see.

Also, in the event that someone from OUR is reading this and feeling litigious, let me make this clear up front: I’m not alleging any illegal activity on the part of OUR. I’m simply reporting what I’ve been told by employees and affiliates, what Lynn has been told in his interviews, as well as what he’s pulled from documents that have either been shared with him or that are publicly available. I don’t have the capacity to verify other people’s testimony myself. The arguments I’m making are based on other people’s testimony, publicly available documents, and material that OUR has printed. I’m just repeating what I’ve seen. It looks compelling, which is why I want it to have a broader audience.

Let’s dive in, shall we?

Claim 1: OUR was started because a nonprofit could do more to effectively combat human trafficking than government agents could.

The origin story of OUR is that it was founded so that Tim Ballard and associates could work independently of US law enforcement after two major events in Ballard’s life: his interaction with Earl Buchanan, and the kidnapping of Gardy Mardy.

I’ve already covered the extent to which Ballard’s report of the arrest of Earl Buchanan doesn’t match customs forms. The evidence is simply not there that Ballard ever questioned this child, let alone received a dog tag from him (which really should have been in an evidence locker if it happened). At any rate, the idea that this incident proved to Ballard he needed to leave the government to fight trafficking is nonsensical. First, this incident happened in 2006, and OUR was founded in 2013. If this incident made Ballard change the course of his life, he definitely took his time. Second, the US government actually did stop Earl Buchanan. Buchanan was stopped at the Calexico port of entry with his neighbor’s child; during a search of the car Buchanan was found to have video evidence of him abusing the boy. The child was taken to a hospital and questioned by CPS; Buchanan was taken into police custody, and he remains in jail today. If Ballard’s lesson from this incident was that the US government could not stop trafficking as effectively as Ballard as a private individual could, this is surprising. Ballard didn’t stop Buchanan’s car or find any evidence; he arrived at the scene sometime later to question and arrest Buchanan in his capacity as a DHS agent. The actual apprehension of the child was carried out by the border patrol.

The second incident is Ballard’s late-stage involvement in the kidnapping of Gardy Mardy. Gardy was kidnapped in late 2009; Ballard became involved in 2013. A blog on OUR’s website and Ballard in media appearances have said that the Haitian government had jurisdiction over the case and therefore Ballard was not allowed to investigate it. This required Ballard to leave DHS and start a nonprofit that had no particular jurisdiction. In actual fact jurisdiction did not seem to have anything to do with this; the FBI was involved in investigating Gardy Mardy’s disappearance and photos of them on the ground exist from 2010 (content warning: disturbing photos). The case went cold because of the 2010 Port-au-Prince earthquake, not because the US could not investigate. The US can and does investigate human trafficking throughout the world – after all, ICE was a partner in Triple Take, an operation that OUR supported. If Ballard was not able to do the world he wanted to do as part of the DHS, this probably has more to do with his position in the DHS, not the limits of the US government’s power abroad.

The actual motive is therefore more complicated. An obvious contender is Ballard’s desire to be personally involved in the search for Gardy. As a DHS agent, Ballard presumably could not demand to be in charge of the Gardy Mardy investigation (which was headed up by the FBI), but as a private investigator he could be involved in whatever capacity the Mardy family wished him to be. And, to be fair, it absolutely does seem that official efforts to find Gardy were stalled or stopped after the Port-au-Prince earthquake.The Mardys’ willingness to team up with someone who wanted to hunt for their son is surely not surprising or blameworthy.

But it seems that another likely motive for OUR’s founding presents itself when we recall their primary claim to fame: namely, their production of flashy media. DHS could investigate sex crimes abroad; what it couldn’t do is make a reality TV series and documentary about it.

The idea that OUR would have a media component where they would gather exciting footage of paramilitary groups bursting in and arresting traffickers seems to have been part of the OUR idea from the beginning. Glenn Beck began promoting this idea in September of 2013. OUR would perform dramatic rescues, and Darrin Fletcher and Chet Thomas from Fletchet Media would film it. This is the joint cause for which Glenn Beck raised money on his show, through donors and investors – not just a child rescue org, but a TV show about them.

That said, this relationship between Ballard and Flechet was complicated. After raising $1 million for the project, Darrin Fletcher and Chet Thomas formed the for-profit venture Fletchet LLC. They filmed a number of OUR operations in 2014 and edited them into a reality TV series. When the show was not picked up by a network, this created a significant financial problem for Fletchet. Investors had poured millions of dollars into the movie and the odds of recouping their investment was slim. To solve this, they edited this footage into the movie The Abolitionists to be released in theaters.

Before the movie was released, Fletcher and Thomas allegedly had a falling-out with Ballard over Ballard’s desire to become a partner in Fletchet and receive payment for the movie. Fletcher and Thomas didn’t want to do this on the grounds that this would create a conflict of interest for OUR (namely, exclusively partnering with a for-profit TV venture where the CEO of the nonprofit was also a partner). This would muddy the water between the for-profit Fletchet and non-profit OUR. Instead the patterns of Fletchet paid Ballard what Fletcher and Thomas made from the movie, about $180-90k, according to Darrin Fletcher. What this relationship demonstrates, from top to bottom, is that releasing media about trafficking and profiting from it was always a core desire for Ballard, from the time OUR was founded.

A third possibility, suggested by a diagram Tim Ballard apparently drew (and since discussed by attendees at said meeting) in 2019 planning meeting, was to get people interested in Mormonism, specifically “The Covenant.” This is a Mormon theory of history/Christian nationalism which posits that God arranged human history in such a way that the United States would always be the home of the one true church, the church of Latter-Day Saints, and that by adhering to Mormon religion the United States will continue to be blessed. You can read an article Ballard wrote about this here.

The diagram (which you can see an actual photo of from VICE courtesy of ACR; I’m using a more-legible recreation of it that Lynn created in one of his videos) was drawn at a planning meeting. The photographer turned this over to Davis County investigators while OUR was under investigation for fraud. The diagram in part seems to suggest that, by making Tim Ballard into an American folk hero, more people will be interested in Mormon nationalism, which he supports. You can see in the photograph that a component of the web of Ballard-controlled for-profits and nonprofits is that all this intention and fundraising is supposed to get people “interested in the covenant.”

A fourth possibility, of course, that becomes very obvious looking at this chart, is that OUR was created to make Ballard a ton of money. The arrival point of Ballard’s planning chart is not, “And then we will rescue hundreds of kids from slavery.” The arrival point is the acquiring of massive speaking fees and millions of dollars for Tim Ballard, under the heading timballard.com. And, this apparent goal of Ballard’s – namely, to make a lot of money – has come to pass. Ballard has made a ton of money, if the 990s are any indication. As we’ll discuss below, a ton of OUR’s money has historically gone to the Ballard’s family – and that’s even before we get to the closely-affiliated for-profits surrounding OUR.

All this is to say: it doesn’t seem likely, based on how OUR has historically narrated its origin story, that OUR was founded because it was more effective at fighting trafficking than US law enforcement. Neither the Buchanan abuse case nor the Gardy kidnapping suffered investigative failures because of bureaucratic red tape or because of the US government’s failure to act. OUR has partnered with the US government for its most successful initiatives.

As we have seen, the idea that OUR would be part-rescue, part-action-movie was part of the OUR concept from the beginning. Ballard was always interested in the media and profit aspect, creating a for-profit company (Slave Stealers, LLC), seeking to be a partner in another (Fletchet Entertainment), and using his nonprofits to bolster timballard.com, where Ballard would make hundreds of thousands of dollars as a speaking celebrity and books. It seems that as long as OUR has existed, the idea of making entertainment surrounding it, and making Ballard a public hero, was part of the plan.

Claim 2: OUR has never found Gardy, but every effort it makes looking for him rescues more kids.

If Tim Ballard has historically been the heroic face of OUR, then the victimized face of OUR is 3-year-old Gardy Mardy, who was kidnapped from the front of his church in 2009. We’ve covered his story extensively in the five-part series on Sound of Freedom and OUR. The claim that the hunt for Gardy Mardy has led to long-term positive outcomes is a common one in OUR material. Essentially, the argument goes that, while OUR has not found Gardy, every time they look for Gardy they find more trafficked kids, because they are pursuing Gardy through networks of child trafficking. Thus, the hunt for Gardy has led to positive outcomes, and no matter how long it takes to hunt Gardy, they will continuously free kids along the way.

I have been able to find three incidents in which OUR specifically set out to find Gardy. Most raids which OUR has staged had nothing to do with locating Gardy and had no chance of recovering him. (There’s a possibility that the raid depicted at the end of the movie Operation Toussaint was meant to get intelligence on Gardy; this is a sting in which a number of sex workers are arrested on the streets of Haiti and are interrogated about who they bribed to get out of prison. No one in the movie answers the questions, and because the connection to Gardy isn’t clear, I’m not counting it as one of the three known incidents).

So that leaves three raids that were intended to rescue Gardy. The first is the raid on Yvrose Pressoir’s orphanage in February 2014. In this raid, OUR in conjunction with the Haitian government launched a sting on Yvrose to catch her accepting $30k in fees in exchange for two children. OUR has historically framed this as evidence that Yvrose was a sex or labor trafficker. However, the footage makes it clear that Yvrose thinks that she is arranging an off-the-books adoption – which has historically been incredibly common in Haiti. I’ve spoken with several Haitians, immigrants to Haiti, and immigrants from Haiti involved in NGOs during the course of writing this series. Some of them even knew Yvrose personally. Most of the people I talked to said that Yvrose would not have kept most of that money, and it likely went in large part to the necessary bribes to get documents to travel with the kids. (Haiti’s government is among the most corrupt in the world; bribes are a normal part of making the public sector work for most Haitians.) So even if Yvrose was arranging illegal adoptions, it’s not always clear how legal adoptions would be different or more transparent. As we’ve noted, legal adoptions have historically taken place in Haiti over the protests of birth parents, or without an attempt to find a child’s parents before the child is sent overseas.

So the extent to which we can describe the children taken from Yvrose’s orphanage as “rescued” is, I would argue, somewhat mixed. Yvrose was not a child trafficker in the way OUR defines the term; there is no evidence that she forged passports for people seeking sex or labor slaves. (The economics of purchasing a domestic worker or labor slave from Yvrose for $10k makes little sense; in a country where most people are unable to feed themselves or their kids, needy children are largely free for people seeking domestic workers, and many trafficked men on sugar plantations go there seeking work.) I interviewed several volunteers and workers at Yvrose’s orphanage, many of whom did surprise inspections, and all of them affirmed that the orphanage was well-run, and the kids were clean and taken care of. The footage of the sobbing children in cribs lying in unchanged diapers that OUR produced comes from the day after Yvrose’s arrest, a day and night during which it is unclear who was caring for the kids when Yvrose was in jail. But footage from before her arrest shows the kids well-groomed and cheerful.

The second raid, the attempt to find Gardy at a child labor camp on the border of DR and Haiti, is the disastrous raid based on a psychic’s insight that is documented in the TV show and movie The Abolitionists, as well as a Vice article about the operation. Ed Smart, father of Elizabeth Smart, was actually on the ground during this incident (this was during a failed attempt at a merger between the Elizabeth Smart foundation and OUR that did not come to pass because of Ed Smart’s frustration with the prevention/rehabilitation wing of OUR); Ed Smart provided a significant amount of information about this operation during later interviews. OUR had gone to the DR/Haiti border convinced that they would find a child labor camp that held Gardy, because they had received this tip from Utah psychic and OUR affiliate employee Janet Russon.

Smart said that the failed mission – in which no child labor camp was located and the group nearly got into a violent altercation with local village leaders because they believed the camera crew was there to scout out natural resources – cost a “horrendous” amount of money. In the footage, you can see that they’ve chartered at least one helicopter. Smart also said that when the mission failed, the group was asked to sign nondisclosure agreements and was told not to talk about what happened. The entire operation seems to have been more the product of mysticism than police intelligence – team members gathered to pray for success at the Mormon temple and sites where M. Russell Ballard (high ranking clergy in the LDS church) had visited, and of course, the tip that the labor camp existed and that Gardy was there came from a psychic. During the course of this mission, no trafficked children were rescued. OUR says that the operation “advanced the search for Gardy,” but it’s not clear what that means – or what it could mean in the context of a search that turned up zero leads.

The third raid attempt to find Gardy was the arrest of Carlos’s brother Wilson in 2018. OUR released the footage in 2020. In the footage the team describes Bristol as “the one who trafficked Gardy.” It is not clear how they got this information, or what happened afterwards to Wilson. Find Gardy hats were available for sale at OUR in 2020, so it seems the search was still underway.

All this is to say: it doesn’t seem to be true that the search for Gardy is continuously rescuing more children. At most, some kids have been moved from one orphanage to another – but as we’ve seen, it’s not at all clear why moving the kids to a different orphanage in Haiti would prevent illicit adoptions. Furthermore, based on the information that is publicly available, the link between human trafficking and Gardy’s disappearance is non-existent. Gardy was kidnapped for ransom, and after that, we have no idea what happened to him. The idea that he was trafficked as a sex or labor slave has never been demonstrated with publicly available data, and Ballard’s suspicions on this seem based largely on information he’s received from prayer, psychics, and, perhaps, the fact that he’d been trying to make a lot of money an anti-trafficking TV show.

According to interviews Lynn Packer has done since, the pursuit of Gardy remains fixated on the Haiti-DR border – or at least it did before Ballard stepped down as OUR’s CEO. If these searches are anything like the one Ed Smart went on in late 2014 – careless about safety, uninformed about trafficking at the Haitian border, overseen by helicopters, and directed by psychics – they probably aren’t rescuing any more kids than the first one did. But they do sound expensive, and photogenic.

Claim 3: The more donations OUR gets, the more operations it can stage, and the more kids it can save.

OUR’s effectiveness at saving kids from trafficking has been mixed. Nonetheless, its track record of making tons of money is not. What is not clear is how much of that money even went towards efforts to help kids, no matter how bad those efforts were.

The strangest thing about OUR is that, historically, it just doesn’t spend that much money on programs. Ministry Watch reports that OUR has accumulated more than $80 million in assets, enough to run OUR for three years. The organization has historically run on an enormous surplus, sitting on resources rather than using them.

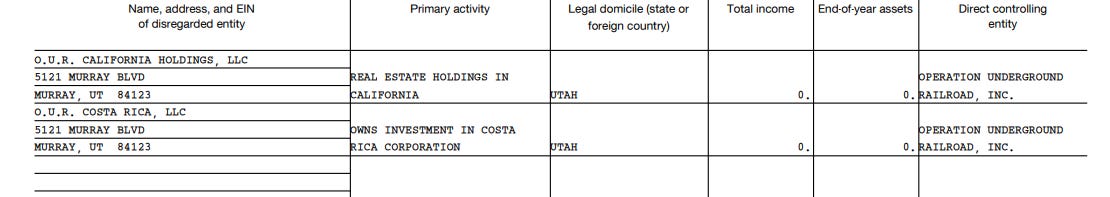

That said, OUR’s spending has increased in the last two years – but a tour of its 990 is not encouraging. Between 2021 and 2022, executive pay for OUR rose dramatically. Tim Ballard himself went from making $335,500 to $525,958. President Brad Damon’s salary jumped from $297,467 to $546,050, and the CFO went from making $246,750 to $379,850. This is absolutely ludicrous compensation for an organization with 128 employees. Katherine, Tim Ballard’s wife, took home $118,283, and their son Blain took home a little less than $50k. The director Mark Blake ($278,684) is Tim’s brother in law, but don’t worry – they set aside time at board meetings to talk about conflicts of interest. A board, incidentally, that includes Blake himself, and Tim’s other brother-in-law, Craig Anderson ($230,534). OUR also has some for-profit enterprises that own real estate and invest in the global south, and they spent more than $4 million on travel last year.

So, before Tim Ballard left, I’d say the best reason to give money to OUR is because you want the Ballards to get paid -- their cut of the pie is pretty impressive. And don’t forget that Ballard’s also got a number of closely-affiliated for-profits.

Another major OUR expense besides the lifestyles of the Ballard family is grants. A large percentage of these go to police departments: either to fund the purchase of a kind of dog that smells USB devices, or to buy Mobile Device Forensic Materials. The effectiveness of these dogs is mixed; Lynn Packer called the handler of one of OUR’s dogs and said that it had actually never found any evidence in a CSAM case. It’s one thing for a dog to be able to find a USB device in a home no one else did (which is played up a lot in press releases that justify the purchase of these dogs), but it’s another for that USB drive to be one that lands a criminal in jail. Sniffer dogs in general are prone to the biases of their handlers, and can create civil liberties problems by performing searches without a warrant. You may not have negative feelings about sniffer dogs, but at any rate, you might not be thrilled that the money you gave to OUR with the idea that it would save missing kids likely made it back to a municipal police department to buy a $16,000 emotional support dog.

OUR also funds purchases of Mobile Device Forensic Materials, which is a software tool that helps police to get your phone data without resorting to a warrant. So if you love surveillance states, but you also want a millionaire in Utah to buy a motorboat, OUR might be a good charity to donate to.

Other massive grants go to organizations that facilitate international adoption. And, of course, OUR spends $1,300,000 on film production and celebrity branding, according to their most recent 990.

So of all the causes OUR seems to support, the most prominent one seems to be fame for some of their higher-ups. The second order of business is promoting the surveillance abilities of U.S. police sources. The third is international adoption.

I personally doubt that we need to give money to private organizations to buy U.S. police more tech – they seem to have enough of it. I definitely doubt that the CFO of OUR needs to make as much money as he does. And while I have extreme concerns about the ethics of some international adoptions for reasons I’ve discussed above: If you care about international adoption, you might as well just give directly to those organizations that support it.

OUR has a long way to go until its finances are transparent and explicable enough to earn donor confidence. And as we’ll see, it’s possible that OUR is doing more harm than good.

This series will be continued in parts 2 and 3.