What Is The Chosen? Part 2-Historical Accuracy

Bonus content: Where did the idea that Passover lambs were swaddled come from?

For Part One of What Is The Chosen?, see here.

Introduction: Theologically Accurate Fiction

One of the major selling points of The Chosen, according to all its supplementary and marketing material, is that it is “faithful to scriptures.” This does not preclude the fact that the majority of the material in the show is, in fact, not from the Bible. Dallas Jenkins acknowledges this. What Jenkins alludes to more often is that the show demonstrates “spiritual/scriptural truth” – the show is theologically true to the Bible even if it’s not textually true to the Bible.

I find this claim to be a tautology. I think what Dallas Jenkins means here is that the show always agrees with Dallas Jenkins’s theology, because Dallas Jenkins made it. I’m sure that’s true. But this isn’t any more insightful of a claim to make about your own writing than me saying “I agree with literally everything on the blog “Not Peer Reviewed! That’s the important thing!” Yes, of course I agree with it. I’m the author.

What I don’t believe is that this show is theologically agreeable to anyone who reads the Bible and treats it as scripture. That seems like an absurd claim to make. For one thing, there’s already the huge problem that The Chosen is adapting four books, not one – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. We don’t see Jesus demanding people to keep every jot and tittle of the Torah in The Chosen (it’s not in the Sermon on the Mount scene). There’s not much of a messianic secret, a hallmark of Mark’s theology, in The Chosen, since the first two seasons follow the Gospel of John fairly closely. Aside from tax collecting and one dispute between Pharisees and Sadducees, economic themes are largely absent in the show – even though they’re a major theme of Luke. The show tends to emphasize the theme of individual faith in Jesus, which is, of course, a major emphasis in modern Protestantism.

I get the impression that Jenkins is aiming for a generalized, ecumenical Christianism that all people who worship Jesus can agree on. The problem is Jenkins doesn’t seem to realize the extent to which this is a product of his American Evangelicalism and isn’t necessarily coherent with the vast number of (significantly older) Christian traditions out there. Jenkins’s roundtables include a Catholic priest, an evangelical academic, and a Messianic Jew, and the production team includes a significant number of members of the LDS church. While all these traditions take the Gospels as scripture, how these churches read the Gospels and accommodate them into larger systematic theologies varies wildly.

So, I don’t see how it can be true that the show may not always tell the stories of the Gospels, but it is always theologically accurate. According to who? When theological lessons that aren’t in the Gospels are introduced, whose theological lessons are these? They can’t be for Protestants, Catholics, and Latter Day Saints. (Messianic Judaism generally drifts theologically towards evangelical Protestantism but I don’t know enough about the various forms to say for certain). We all have different theologies. We all read the Bible differently and incorporate other sources on how to think about it (yes, you do too, Protestants). So I don’t think it’s true when the show takes a dive into invented stories and themes that aren’t dominant in the Gospels (money, marriage, infertility, chronic illness, etc) that Jenkins’ take on these theme is just generally Christian.

So as far as the invented material goes, I struggle with the idea that it’s theologically accurate for a general Christian audience. I don’t even know what that would mean.

But what about the history?

Part One: History, Scripts, and Dallas Jenkins - Who Does the Buck Stop With?

Jenkins says that the first step in writing the show is consulting the Gospels, and prayer. He emphasizes that the show does not first depend on tradition or history. Then the scripts are sent to the script consultants. More on them to come. The two questions he asks are, if a scene happens in the Bible, “did this happen.” Then, if they are adding something to it, the question is, “is this plausible.”

So here’s the thing: this is just clearly not what happens.

First, the claim that the show is based on the Gospels over church tradition, and things are added only when they are historically plausible. That’s just not true when it comes to naming the (presumably) Jewish woman who grabbed Jesus’s cloak “Veronica.” It’s not historically plausible that that woman’s name was Veronica. Veronica’s name means “true icon” (vera icona) in Latin – she is named for the image of Jesus that, according to church tradition, she miraculously preserved on her veil when she wiped Jesus’s face on the via dolorosa. But this is a Latin name, not a Jewish woman’s name. If she’s not Jewish, this raises the question why she would be (as she apparently is) aware of the purity issues surrounding touching Jesus while bleeding. Whatever the bleeding woman’s name was, it definitely wasn’t Veronica in historical fact.

What could have been historically plausible is that the woman has the closely related name of Berenice, from the Greek for “bringer of victory.” This would have been a good choice because Berenice is a name attested in the Herodian dynasty – Berenice was one of the nieces of Herod the Great. But the name Veronica itself does just come from church tradition. It’s not historically plausible. And that’s fine. It’s just not what Jenkins says happens when they write a script.

Second, there’s the breakdown between the consultant and the production team. There’s nothing in a consultant’s contract that necessitates that the production crew must take your suggestions on board. Jenkins can say all he wants that they ask his consultants key questions about accuracy and plausibility, but there’s actually pretty good indication that sometimes he doesn’t actually use the feedback at all.

One is in the roundtable for The Chosen 1.1 (roughly minute 16), when Jason Sobel strenuously denies that Peter would have fished on the Sabbath, and insists that a devout Jew would not have broken Sabbath the way a Christian American dad might skip church. This is apparently why Peter fishes on the Sabbath in the original script. (This strikes me as the kind of note that in publishing comes from a good sensitivity reader, which is good work by Sobel). To Jenkins’s credit, Jenkins says that he tried to “meet (Sobel) halfway” and come up with a situation where Peter would have done this out of desperation – but the fact that Sobel had to fight this pretty hard, and that fishing on the Sabbath still happens in the final script, is pretty telling. Sobel still says in the roundtable that Peter would not have done this, even out of desperation. This does cause one to wonder – when disagreement is less strenuous, are the consultants’ thoughts being ignored?

There are two more of these instances in the roundtables where a consultant challenges something in the script he had already reviewed. These are both in Roundtable Episode 3.7, and they’re both from Jason Sobel again. First, at about the thirty minute mark, Sobel says that the characters in The Chosen say you can’t drink the water in the Sea of Galilee. In actuality, the Sea of Galilee is just a big freshwater lake and you totally can drink the water. Jenkins argues that because of the fishing and weeds you wouldn’t want to just get the water right out of the side of the lake, but acknowledges this may have been an error. Secondly, at thirty-one minutes, Sobel points out how unlikely it is that Shammai would have been the head of the beit din in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus’s ministry, since Shammai died in 30 C.E. Again, Jenkins notes that Shammai is being used as the face of Jewish opposition to Jesus. This is, arguably, ecumenically safe territory since rabbinic Judaism follows Hillel over Shammai, and making Shammai a bad guy is not as objectionable as another rabbi might be (that’s not what Jenkins says, but I think that has to be the motive here). Nonetheless, if we think Jesus died around 30 C.E., it’s hard to imagine a near-death Shammai scheming to bring down Jesus. He probably had other things on his mind, like dying, or being dead.

So it seems like, though the consultants are asked what is plausible and what is not, sometimes implausible things get in the show anyway – even when the consultants object. That means that the person we can ultimately assign the material to is, above all, Dallas Jenkins. And if I can put my cards on the table here, Jenkins has some real moments where it sounds like he makes some really odd choices about the Bible. He has a very obvious evangelical background and he studied the Bible in college. Nonetheless, there are a few stray details here and there that make me think Jenkins gets a little mixed up now and then.

Here are some odd things I’ve heard Dallas Jenkins say that suggest some possible unfamiliarities with the source text:

Jesus Wouldn’t Heal Whole Towns He Got Asked To Heal

This is part of Dallas Jenkins’s apologia for Ramah’s murder, and I have to be honest I have absolutely no idea what he’s talking about.

At 1:10 in this livestream Jenkins talks about the “hard truth” that “Jesus didn’t heal everyone.” That’s actually pretty misleading. Today, Jesus doesn’t heal everyone. But there’s no reason to think Jesus is ever portrayed in the Gospels as sometimes healing someone and someone deciding not to.

The Gospels are actually pretty insistent Jesus did heal everyone who asked. Matt 4:24 says that throughout Syria they brought Jesus “all” those with diseases and demons and Jesus healed them. When Jesus withdraws into Galilee in Matt 12:15, many continue to follow them and he heals them all. Luke 4:40 makes a similar claim that Jesus laid hands on “every one” who was brought to him and healed the people in Capernaum.

But Jenkins digs in further and says at 1:11 that there were times when people would ask Jesus to perform a healing but Jesus would need to move on. I have absolutely no idea what Dallas Jenkins is talking about. The only real candidate I can think of is Nazareth, but this isn’t nearly as mysterious as Jenkins says. In Matt 13, Mark 6, and Luke 4, Jesus does not perform miracles in Nazareth because he and his message are rejected there. The closest parallel to what Jenkins is talking about that I can think of is Luke 4, where Jesus reflects on miracles done to gentiles but not for Jews in the Hebrew Bible. But this is not really a claim about how Jesus operates generally – picking some and rejecting others for healing. He is refusing to privilege his own hometown (which will become a major motif for the gentile mission) for healing, and for that he’s attacked.

I can only think of one place in the Gospels where someone asks Jesus to stay, and that’s the Shechemites in John 4:42. But then Jesus does stay, and he leaves because everyone in the town comes to believe. He doesn’t leave unfinished business.

There’s only a few stories where Jesus doesn’t go somewhere. Luke 9:53 depicts Jesus attempting to go into a Samaritan town, but again, this is because they reject him, not because Jesus rejects them. I just don’t know what part of the Gospels Jenkins is talking about.

Thomas Wanted to Go Die With Lazarus

I think I could be wrong about this but Thomas’s line in The Chosen 4.6, when the group learns that Lazarus is dead, suggests that there is some ambiguity in John 11:16 when Thomas says “let us go with him, that we may die with him.” In the show Thomas says “we might as well go to the house of Lazarus, that we may die with him.” When he says the last part, he looks directly at Jesus, not the disciples.

In John 11, though, Thomas is (I think) unambiguously talking about dying with Jesus. The disciples are hesitant to go to Bethany because people there are seeking Jesus’s life. Thomas is encouraging them to go die with Jesus, which Thomas sees as a real possibility. There is no indication that Thomas means that they might as well go die with Lazarus.

So the line seems to suggest having given up on life and being ready to die in The Chosen, Given that the explanation for Ramah’s death in the show is that this explains why Thomas became the way he was, this is actually a pretty big deal. If Thomas expresses a sudden desire to die with Lazarus, then yes, this is a suicidal character, which seems to be the motivation between Dallas Jenkins apparently asking the question “why does Thomas want to die?” (He doesn’t, he flees with the rest of the twelve). If Thomas is, however, saying that he is willing to follow Jesus to the end, that doesn’t necessarily fit with the fact that Thomas also thinks Jesus let his fiancee die for no reason.

I think this plotline hangs on how you read John 11:16, and I don’t think Dallas Jenkins reads it the way it should be – as Thomas declaring his allegiance to Jesus. I think Jenkins reads it as a suicidal declaration, but it isn’t.

“Veronica’s Name Isn’t In the Gospels, At Least.”

I could be reading too much into this but this is at 24:59 when Jenkins refers to the name of Veronica, the traditional name of the woman with a flow of blood and who wiped Jesus’s face at the cross. Jenkins says that her name is “not in the scriptures, or the Gospels, at least” which makes me think he thinks it might be in Paul or another epistle. It’s not. We’ve already talked about why. It’s not plausible that a woman named Veronica was the woman with the flow of blood.

This is also a bit of an aside, but: Jenkins seems a little dismissive of his Catholic consultant when Father Guffey explains the significance of Veronica’s veil. Jenkins then jokes about how many churches claim to have the Veil of Veronica, to which the answer is: one, Dallas. It’s in the Vatican. The Catholic Church is centralized, and they keep track of relics. There are other Holy Faces of Jesus around Europe and the veil is said to have been carved into pieces that also reflect the face of Christ through a miracle. This is how Alicante got their piece — the Holy Face of Alicante. You don’t have to believe it, and you can think it’s dumb. But it’s not any sillier than thinking the Gospels completely agree with each other. I don’t know. It rubbed me the wrong way.

And of course we’ve already discussed at length the fact that Dallas believes things that are demonstrable Bible turkeys, like human sacrifice at Caesarea Philippi and that anointing the Passover lamb’s feet is a well-known biblical tradition. Both of these are wrong.

So this leads up to the three historical consultants. Is this actually the best crew for the job? We’ve got three men in the hot seat here (and yes, they are all men, which explains a lot about The Chosen’s pervasive fridging problem). They are Doug Huffman, David Guffney, and Jason Sobel. And of the three, only one really has a strong claim on the label of “historical expert on the New Testament” by the standards we use in academic historical spaces.

So who’s our team?

Part Two: The Historical Consultants

Consultant Number One: Dr. Doug Huffman

Doug Huffman is an honest to God professor of New Testament studies who received his Ph.D. in New Testament at Aberdeen and teaches at the Talbot School of Theology in California. If you like academic experts on the New Testament consulting for The Chosen, Dr. Huffman’s your guy, because he’s the only one. Of the three consultants, Huffman is the only one who has a terminal degree in the New Testament. The only one.

So you all out here coming for me saying that Jenkins has this really deep bench of academic experts who advise the show – no. They don’t. It’s Huffman. That’s it.

I haven’t read a lot of his work, but I know people who studied with Dr. Huffman and I have no reason to think he’s bad at his job. Huffman’s actually done a fun job now and then stopping Jenkins from saying something boneheaded in academic roundtables. For example, he cuts off Jenkins pretty hard when Jenkins tries to use Greek to explain that Peter’s name Petros means “a small rock,” as opposed to “the big rock” (petra) of Jesus. The source for this claim is archaic references in Homer and Euripides where a petros is distinguished from a petra. As far as I know, though, this convention doesn’t exist in Koine. The better explanation for why Peter’s name is Petros, not Petra is because Petra is feminine.

On the whole, in the roundtables, Huffman comes across as diplomatic. He’s not trying to ruin the party as people around him say truly bonkers things (he’s really, really quiet when Sobel and Jenkins are getting into the idea that Caesarea Philippi was a site of human sacrifice in the roundtable for 4.2, which makes me suspect he knows better). But he also does try to keep some objectively wrong things out of the roundtables.

Consultant Number Two: Fr. David Guffey

The Catholic representative is Father David Guffey, C.S.C. Father Guffey’s background is in pastoral ministry, media, and television production. He is a priest in residence at Congregation of the Holy Cross and the national director of Family Theater Productions.

Given that Father Guffey’s background is more in television than history, it actually makes a lot of sense why he’s useful at a roundtable for a show. He knows a lot about the practicalities of film production. Unfortunately, you don’t really hear a lot from Father Guffy in the roundtables. I don’t know if he’s naturally quiet or if the edit doesn’t favor him. Father Guffey is usually listening but he’s able to make some helpful contributions. He brings up the question of Peter’s celibacy and the role of popes in this video. However, it’s noticeable that Guffey’s feedback seems to skew hard towards the pastoral and relational, and about Catholic tradition. For instance, Guffey does a good job de-mystifying the idea of Catholic exorcisms and noting that the church rarely performs these. Guffey’s comments also skew towards the technical and artistic – which makes sense, because Guffey has an MFA from Loyola Marymount University, and film production seems to be where he spends most of his time. This is useful expertise, but it’s not really the same thing work that a first-century historical consultant would do.

I don’t doubt that Guffey knows a lot about the Bible and the New Testament, at least to the extent that any priest must know it. But I don’t really ever hear him get into the historical weeds that a more academically oriented priest would be able to navigate. And there are a lot of priests with doctoral degrees who teach at colleges and work on biblical history – not to mention the many, many Catholic scholars who do the same. I actually did my doctoral degree with a priest, my former colleague Rev. Adam Booth, Ph.D. – and he’s an incredible scholar. (Mr. Jenkins, in the unlikely event that you’re reading this – if you’re looking for a kind heart and brilliant historical mind among the Catholic priesthood, Adam’s your guy.)

There’s nothing shameful about not being a historian, or not having extensive graduate experience in the Bible or New Testament studies. It’s probably beyond the workaday necessities of the average Catholic priest. But if you want someone to provide historical insight into a script, and fact-check claims made in the text, you probably need someone with more historical-critical experience than Father Guffey seems to have – or frankly, more than he needs to have to do pastoral care and film production. I’m not saying Father Guffey can’t be involved – as I said, he seems like a great sensitivity reader for Catholic viewers and he is able to represent a Catholic perspective and prevent bonus content from making false claims about Catholics. But I’m not really sure he’s the guy for the job if you want a historical fact checker.

Consultant Number Three: Rabbi Jason Sobel

Okay, get comfortable, because we’re going to be here for a while.

Rabbi Jason Sobel is a Messianic rabbi and the Jewish consultant for The Chosen. Rabbi Sobel is ethnically Jewish and was raised in a Jewish family, and became a Messianic Jew at the age of eighteen through a mystical experience. He was ordained by the Union of Jewish Messianic Congregations. He is now the director of Fusion Global, which is one of those places where (stop me if you’ve heard this one) you can buy study guides and lectures to learn more about the Jewish roots of the New Testament.

Sobel received a B.A. in Jewish Studies from Moody Bible Institute and an MA in Intercultural Studies in Southeastern University, which is a Southern Baptist school. This M.A. degree includes training in biblical studies, Baptist history, apologetics, Christian ethics, and practical teaching for ministers (contextualization, church management, etc.). My Jewish readers may be having a bit of a hernia at this point about how Baptist this rabbinic education is (I did run this resume by friend of the blog and now-regular rabbinic consultant Meir Simchah Panzer), and on that subject, I am simply not fit to comment. I bring this up to contextualize Rabbi Sobel’s involvement in the show, not to delegitimize him as a rabbi. As a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant lady, it is not my place to decide who is or isn’t a rabbi. That is something rabbis can decide amongst themselves. My interest is in who has historical education, and what kind.

Rabbi Sobel must have taken some other graduate courses in order to get his ordination from the UMJC, but if you look at the ordination course list, you’ll see this is still a pretty pastorally-oriented course list. I’ve taken one graduate course on the Talmud, and I’m not even close to being ready to advise on a historical project involving it.

I don’t doubt that by growing up in Jewish spaces and by virtue of his training that Sobel knows a lot more about Judaism, particularly its more contemporary forms, than I do or anyone else at those round tables. The vast majority of feedback Sobel gives in roundtables is cultural and social, pertaining to contemporary Jewish communities and Israeli practice and noting ways in which the show avoids making the characters not seem like American Protestants. This is important. However, I am not convinced Rabbi Sobel is ready for prime time when it comes to biblical history. I gave Sobel a ton of credit for pushing back on historical inaccuracies in the roundtables, and I meant it. He is good at catching things that ring false to someone who is Jewish and spends a lot of time in Israel.

But let’s talk about his books.

Mysteries of the Messiah (2021) and Signs and Secret of the Messiah (2023)

I checked out two of Rabbi Sobel’s books from the library and a lot of it is, I would argue, fairly boilerplate pastoral insight into biblical texts. The first chapter of Signs and Secrets of the Messiah is about Jesus’s miracle at Cana talks about the marriage between God and his people, and the importance of asking God for what we need and depending on him. Jesus’s healing and feeding of people points back to God’s provision to his people at Sinai. Etc. There’s also some good intro-level historical details – because this is a popular level book, and these are necessary – like explaining the schools of Shammai and Hillel, the Pharisees and the Saducces, etc. This is useful material for a general audience and it’s good to include it. This is all very consistent with Rabbi Sobel’s education and experience. The writing is very pastoral and encouraging, with some entry level history to help people find their way around the references. Nothing wrong with that.

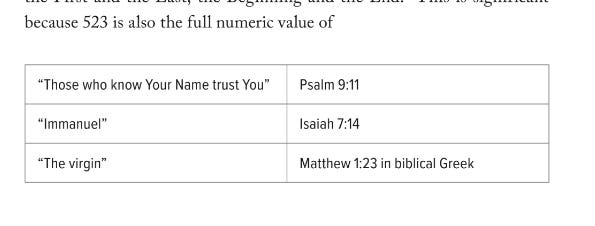

But one thing you’ll notice really fast if you read both of Sobel’s books is that there is a ton of gematria in these books, and in his media generally. A ton. Numbers are everywhere. Now, this isn’t an inherently illegitimate practice for reading the New Testament. There’s gematria (or figuring out the numeric value for every letter of a word and adding them together to make numbers) in the first chapter of Matthew (the numbers of generations spell “David” – this is in chapter 12 of Mysteries of the Messiah) and most famously, the number of the beast in Revelation.

Sobel insists that gematria and finding links between numbers is not for creating new doctrines, but for getting deeper insight into a biblical text. On this front, I have to be honest that I just don’t see why this is meaningful. There are absolutely symbolic numbers in the Bible – twelve tribes/twelve disciples, for instance. But a lot of these numbers don’t seem to be inherently meaning-making. For instance, Sobel is interested in the fact that there are six stone jars in John 2 used to store the water (which will become wine) at the wedding of Cana. Six is the number of humanity, because it’s the sixth day of creation. Thus, there are six pots because Jesus is the second Adam.

You don’t need six stone pots to arrive at “Jesus is the second Adam.” Paul will tell you that. And, it’s not at all clear John actually intends to communicate meaning through these numbers or that they would have been readily apparent to his audience. There’s a famous story about John scholar Raymond Brown on John 21:11, which the story of the disciples miraculously catching 153 fish. When asked why John reports such a specific number, and what its symbolism might be, Brown said John would likely tell us that that’s how many fish they caught. Why did John write that there were 153 fish? Well, because there were 153 fish. (I heard this story from my advisor Joel Marcus, who, when Raymond Brown was dying, reminded Dr. Brown to ask John how many fish there were). So by the same logic – why are there six jars at Cana? Well, because that’s how many jars they had. Do you really have more insight into thinking about the importance of six?

These are all over Sobel’s books. “Cross” and “leper” have the same number. “Grain” and “harvest” have the same number. “Cross” and “grain” have the same number. Do you feel more insightful about the Bible? I can’t say I do.

This page from his Facebook is actually a pretty good example of a lot of his writing. You might be into that kind of thing. I can’t say I am. But as I’ll show you, it’s not even good gematria, anyway.

I don’t really know what spiritual insight I’m supposed to get out of this. Passover was God’s victory over Egypt? I got that from reading Exodus. What am I supposed to do with this repeated invocation of 148? Use it as a PIN for my bank card?

There’s some sneaky changing up of the languages, though, in that last one – you’ll notice that all the words are Hebrew until we reach “promise,” and then that’s in Greek. There’s also some additions of prepositions and suffixes to make the math word. The word for “iniquity” is avon, but Sobel has bavonkah/bavonkh, which is “in his/her iniquity.” The word for “plague” also has a preposition – “plague” itself is maggephah but Sobel has added another preposition – “like a plague,” or “as a plague.”

But even if you don’t play fast and loose with prepositions and suffixes to get the math to work, what’s the point? That “promise,” “plague,” and “Passover” are all related concepts?

Here’s another. The Greek word for “lamb” isn’t arnas. It’s arnion, or amnos. Sobel has pulled the plural accusative form from Luke 10:3 here of aran (which is a comparatively rare word for lamb in the New Testament and only appears in that verse) – so not “lamb,” but “direct object lambs” (sort of. We can talk about Greek cases another time). Likewise, lekevesh isn’t the Hebrew word for “lamb,” either. It’s a preposition attached to the word “ram,” kevesh, so “to a ram.” (Rams aren’t lambs, by the way.) The final sigma in the Greek word for “Mary” is wrong – that changes the math in some gematria systems, and also he’s using the genitive form of “Maria” here, so that’s not “Mary,” that’s “of Mary.” The math for “Miriam” in Hebrew doesn’t work out – it should be 290 by Sobel’s count, not 352. Finally, the Hebrew word for “to draw near” is qarab, not karav, and qarab’s is 302. You would need to add a nun to get to 352, which would make the stem niphal instead of qal and mean “to be drawn near.”

Anyway, all this math and letter-fudging is necessary to get us to the longitude of Bethlehem, which has been determined relative to our modern Prime Meridian, which passes through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich and was established as the Prime Meridian at the International Meridian Conference in Washington, DC, in 1884.

Do you understand Christmas now? No, of course you don’t.

I used Sobel’s gematria chart that he provides in the appendix of his books, and I tried again and again to get his math to work without success.

This is from the intro to Mysteries of the Messiah. I got, respectively, 503, 191, and 329. I invite all of you to check the math yourself. It’s possible I was using different spelling than he was or that I just suck at math, but honestly, this seems like a pretty good reason to think that gematria isn’t that helpful for looking into the New Testament as a matter of course. At best, you’re going to find out some words are related. At worst, you’re going to find out that they’re not. There may be a cultural barrier between me and Sobel here – he clearly is a mystic, and I understand that these kinds of sacred numbers are often useful in this kind of devotional practice. But I’m not really seeing good textual insights in this material.

My point is, this is an odd choice of subject to spill a lot of ink on. It’s possible – indeed, probable – that Sobel finds this meaningful. I don’t have anything personal against the guy, and I don’t have any reason to think he’s being insincere. But none of this is suggesting to me that he should serve as a historical consultation on a show set 2,000 years ago.

In fact, when it’s time for Jason Sobel to educate people on history, there’s at least one incident where he completely botches it. And that’s Sobel on the Christmas story, as we’ll see.

Rabbi Sobel and Passover Lambs: Christmas Version

Okay, so here’s where I’m going to sound a bit mean.

I am not trying to come for Rabbi Sobel’s gig but I do have to make a point of this: Sobel has gone on record producing video content for The Chosen putting his authority behind what is demonstrably a “Bible turkey.” By “Bible turkey,” I mean “widely publicized total nonsense about the Bible.” I’m not talking about the Caesarea/Gates of Hell thing (which Rabbi Sobel agrees with and amplifies in Roundtable 4.2, and is also bad). This is the widespread hacky Bible myth that the shepherds were able to recognize Jesus as the messiah because they were levitical shepherds and saw Jesus wrapped and placed in a manger like a newborn sacrificial lamb would be. This is completely false.

Let’s roll the tape. Jason Sobel talks about being in the field in which the angels apparently went to visit the shepherds in Luke 2. Where Jason Sobel is standing Migdal-Eder. He tells us these shepherds were “levitical shepherds” who are raising their sheep near Bethlehem specifically for the sake of raising the sheep that would be sacrificed in the temple. Sheep giving birth to lambs would be taken to a nearby, ritually clean cave, and then the lambs would be swaddled and placed in mangers so they didn’t break their legs shortly after delivery. Then, when the lamb calmed down after birth, it would be unwrapped. So, when the shepherds were told to find a baby wrapped in clothes lying in a manger in a cave, as levitical shepherds they would have immediately realized that this baby was the ultimate Passover lamb.

Sobel is repeating a mix of lightly sourced historical speculation, as well as recently invented myths – as I’m going to argue. These are all stories that get bred and spread with Israel tour groups, apparently.

This claim that the shepherds were at Migdal-Eder (which means “tower of the flock”), and their flocks were specifically for sacrifice, probably comes from Alfred Edersheim’s 1883 book The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. Edersheim argued that early Jews believed that the messiah would come from Migdal Eder. He gets this from Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Gen 35.21. I’ve also seen this claim attached to Micah 4:8. Edersheim thought that the field of Migdal-Eder was used for shepherding sheep that would be used for Temple sacrifices based on the Babylonian Talmud (b. Baba Kama 7.7 and b. Baba Kama 80a), which say that one cannot raise flocks in Israel, and the Mishnah (m. Shek. 7.4), which says that the animals in and around Jerusalem (including Migdal-Eder) should be assumed to be from Jerusalem because the town is primarily full of sacrificial animals. Therefore, since Jews were not allowed to raise sheep and goats in the land of Israel, the only reason why shepherds would raise sheep and goats is for sacrifice, and they must have been doing it at the Tower of the Flock.

The claim that people didn’t keep sheep in Israel unless they were sacrificing them is, I think, pretty far-fetched. Ordinary people clearly have sheep in Matthew 12, and there’s no indication that these sheep are specifically for sacrifice. Josephus also recounts many stories about shepherds in his Jewish Antiquities without noting that shepherding is no longer permitted in Israel. So for that reason, I think the idea that the only place Israelites were allowed to keep sheep in Israel was for the purpose of sacrifice (during Jesus’s lifetime, at least) is hard to believe. Also, Luke doesn’t say anything about Migdal-Eder. Even if we think that this Mishnah passage alludes to the idea of sheep for sacrifice near Migdal-Eder and Jerusalem, we’re still assuming that the Talmud is correct that these are the only sheep in town. This is a later source than the Gospels, who don’t seem to demonstrate knowledge of this tradition, and to me looks highly implausible. The sheep could be any sheep. The shepherds could be any shepherds.

Second, there’s the idea that the lambs, and Jesus, were born in ritually clean caves. The idea of a “ritually clean birth cave” for a baby boy doesn’t make sense. As soon as a woman gives birth in a cave, it’s not a ritually clean space anymore, because childbirth isn’t clean (Leviticus 12). Her clothes and the material she sat on would be unclean from the birth itself. Also, Jesus isn’t even born in a cave in the New Testament. The cave comes from the Infancy Gospel of James, which is probably a second century text. The place where there is no space for Mary and the baby in Luke is the kataluma, or guest room – the same kind of place where Jesus eats the Last Supper (Mark 14:14). (It’s not an inn, actually). If Mary and Joseph aren’t able to access a guest room, this probably means that they’re on some kind of private residential property, but are not able to find suitable privacy or comfort in the guest room of the house. So, Mary is by the manger, which could be a portion of the home where animals stay (Kenneth Bailey in Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes argues based on archeology and modern rural Palestinian housing that the manger is actually in the main house, which would put Mary in the living room), or perhaps some kind of outbuilding or shelter. It doesn’t follow that, if they were unable to stay in the guest room of a friend or relative in Bethlehem, that Mary and Joseph would leave Bethlehem entirely and go stay in a cave.

But what about the claim that the sheep would be bundled and placed in a manger immediately after birth? Were the swaddling clothes used to wrap lambs?

Dr. Gary Manning Jr. did a word search for “swaddling” (which Mary is said to do in Luke 2:7, σπαργανόω) to see if he could find any associations between swaddling and animals. The act of swaddling, as far as Manning was able to find, is only associated with babies, not with animals or sacrifices. I wasn’t able to find any exceptions when I looked myself. The emphasis here is probably less on animal husbandry and more on the humility and ordinariness of Jesus. Ian Paul actually notes that there’s a fascinating parallel in the Wisdom of Solomon about being wrapped in cloths, as a sign of “normal babyhood.”

Is it plausible you would temporarily wrap a lamb after birth? I don’t think so. For one thing, it doesn’t make any sense. You don’t sacrifice baby lambs at the temple, you sacrifice yearlings. Even if the lamb is guaranteed not to break its legs for the first twenty minutes, you still have a whole year to get through. Newborn lambs may be carried by pack mules in the traditional manner of the transumanza in Italy today, but that’s because of the difficulty of carrying them up and down mountains, not because of the excessive friskiness of the immediately newborn lamb. The lamb is not exceptionally breakable for seven to ten minutes after birth, nor exceptionally active.

It also doesn’t fit with the lambing process. For this my source was my aunt Sally Bassford, who is a veterinarian trained at Purdue University (as an Indiana University grad – boo!) and she was able to answer some of my questions about lamb birth. Dr. Bassford said that there is no need to immobilize a lamb after birth to prevent injury. A mother sheep will begin the process of cleaning the lamb after birth – lambs are caul eaters, and immediately after birth consume the placenta and caul of the baby. After the ewe cleans her baby (or babies, multiple births with lambs are common) the lamb will then use its legs and stand up. Wrapping the lamb for the period between birth and standing just delays the natural process of the lamb standing and nursing that otherwise needs to occur for the lamb to be healthy.

Nonetheless, this myth has become exceedingly popular in Christian media and online spaces in the last ten years or so. A major popularizer for this story is Christy Nockel’s 2016 song “Wrap This One Up,” which incorporates the theme of wrapping a sacrificial animal into the nativity story. As widespread as this story of swaddling lambs is (and it even gets fancier when we add the detail that the lambs were specifically swaddled in de-commissioned priestly vestments, as in the narrative of The Chosen) it needs to be stated there is absolutely no historical reason to suppose this happened. This is complete nonsense. There is no textual evidence in Luke this was the case. There are no Second Temple sources that claim this. There are no rabbinic sources that claim this.

The earliest source I can find for this claim is a man named Dr. Jimmy DeYoung. Dr. DeYoung of blessed memory produced a trail of sources where he tells basically the same story that Sobel does – that the lambs would be born at Migdal Eder, born in caves, wrapped in fabric, and placed in mangers (though in his documentary, DeYoung also hilariously reenacts it with a guy in a stupid costume and a stuffie).

Jimmy DeYoung was a television and radio star who produced and narrated lectures about the Bible on the show/online channel Day of Discovery (now Our Daily Bread ministries). DeYoung’s education and experience was primarily in journalism and broadcasting, though he did get a PhD from Louisiana Baptist University in 2000, where you can get a degree in Advanced Prophetics (do they stone students who fail their comp exams?). And no, that’s not a historical and theological course in classical prophecy as a genre. It’s about how to predict the future.

I can’t find a lot about Jimmy DeYoung’s academic experience except, you know, all that. And, that he supervised a master’s thesis on whether or not we are living in the end times, which I would not usually consider to be a historical subject. Given that the nature of the question can only be satisfactorily resolved by the end of the world, I’m not really sure how the defense went when the hour concluded and the world was still there. All this is to say, I’m pretty sure he didn’t have some amazing Syriac source that I can’t read.

In its Jimmy DeYoung form, this swaddled Passover lamb claim appears in a documentary from 2009 but this story is at least as old as 2006 where it appears in the comments on this blog (though the body of the blog itself has another stupid turkey in that the swaddling clothes were actually on hand to wrap Joseph if he died on the trip). It also shows up in this citation of a 2005 email newsletter by DeYoung.

That makes this email from DeYoung the earliest available textual source. His email includes no source.

Before 2005, there are no sources available on any search engine. There are also no hits in Google Books or any academic source I can find. This makes DeYoung the earliest discoverable source for this claim, at least as far as I could find. It is possible he heard it from a textual source (like a tract) that has not made it into digital archives, and it’s also possible that he heard it from an aural source. Or, he could have invented it himself.

But at any rate – if DeYoung is the historical source for the “swaddling the lamb” story (and he’s the earliest I can find) it’s safe to say that DeYoung deserves a spot in the Laura Robinson Hall of Cranks. He never provides any sources for these claims and his interest in history seems centered on history that hasn’t happened yet. This may be another suspected incident of people using historical texts and goosing them up with charismatic insights, which I’ve already argued The Chosen may be susceptible to.

I can’t find a source for this claim before Jimmy DeYoung. It is possible this is a misunderstanding of the more popular canard that a corpse is also wrapped in cloths, so Jesus was marked for death as soon as he was born. (Of course, by this logic, Jesus was not any different from any other swaddled baby). Or it may come from a misunderstanding of a motif that I can trace back to a Jonathan Edwards sermon, in which Edwards says that Jesus looked like a lamb in his swaddling clothes. Edwards, though, is referring to Jesus’s meekness and temperament here. He’s not making a literal comparison between Jesus and a lamb. The claim seems to have its earliest origin with DeYoung, who either made it up or misunderstood it from someone else.

But here’s Rabbi Jason Sobel, historical consultant for The Chosen, making this claim as though it’s a historical argument.

It isn’t!

Honestly, to see one in three historical experts for The Chosen voice a historical claim without providing a source makes me more than a little concerned. It makes me even more concerned that I can’t find one for him. I hate to be unkind but it’s not clear if Rabbi Sobel knows how to verify or research these kinds of claims or if he really attempts to. Jason Sobel’s also on record repeating the extremely dodgy claims I’ve already debunked about Caesarea Philippi, which he makes in the roundtable for Episode 4.2. I’m not trying to be unkind — and again, there is nothing shameful about not being a professional historian or having extensive graduate experience in ancient studies. But, it seems like he’s more than a little prone to repeating claims he’s heard without looking into them. And when your job is to be the person who provides historical feedback for a show, that’s just not enough.

Conclusion

I think there’s a gap between what fans of The Chosen want to believe about the accuracy and plausibility of the show, and the role of experts, and what seems to be the case. The argument that the consultants are experts of biblical history is simply not there. Only one person seems to have extensive academic experience with history, and one of the consultants does not seem to know how to defend and source historical claims.

If a major selling point of the show is historical accuracy, and fans are under the impression that the historical claims made in the show itself and the supplementary material are exhaustively resourced and sourced, this may actually not be the product that’s ending up in the tin.

As I’ve said many times, I enjoy the show a lot, and I want it to be good. But I think some changes need to happen to the historical side of things to prevent The Chosen from becoming a Bible myth superspreader.

My Solution

In the event that anyone from the show is reading this, and based on the extremely positive interactions I’ve had with the team from The Bema podcast after I did a similar review of their work, allow me to provide some ideas about how to improve The Chosen and specifically its supplementary content.

More Historical Rigor Among the Consultants and in the Aftershows/Roundtables

The roundtables would be improved tremendously by the addition of academics to the pool, even if they’re behind the scenes. Right now, the only academic historian of the four is Doug Huffman.

I am not saying this to be unkind to Jason Sobel and David Guffey. I am not saying they are stupid. They don’t have to get kicked off the show. They do provide insights, and they represent important perspectives. But it’s time for Dallas Jenkins to call in some historical backup and actually listen to it. Right now, it seems like the major fact checker for the historical world of the show is one man. He can’t catch everything and he can’t pick every fight. There are hundreds of amazing scholars of the New Testament, the ancient Mediterranean, and early Judaism who would be far better suited to the work of historical fact checking than these three alone. You can find such scholars with Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant backgrounds,

Embrace Perspectivalism and Imperfection

This is a show made by a largely American team with American sensibilities. Obviously, localization is going to happen in the translation and dubbing process overseas, but the idea that the show represents a general Christian perspective is incoherent. The Chosen does not have to be the definitive portrayal of the Gospels for all Christians. That’s impossible. In twenty years, even the dialogue style, performances, and humor of The Chosen will be dated. The style right now is in conversation with modern American media, and what Americans like to see.

If Jenkins et. al. can set aside the self-imposed burden of this show being generally true to a generally Christian audience, they can talk about it in a way that sets a more reasonable standard for fans. Right now, if you’re being promised that the show is theologically accurate for all viewers, you’re going to invite real problems when things in the show happen that don’t feel theologically accurate. (Like Jesus’s somewhat flaccid defense of Ramah’s murder).

And, you create space for people to go do their own investigations. If the show has to be accurate historically and theologically, this puts pressure on people to repeat things that are really silly – like saying that Exodus 12 talks about anointing a Passover lamb when anyone can see it doesn’t. If you can just say that you heard it in a sermon and you liked the idea, then you can admit it might not be true, and discourage people from feeling defensive about information that suggests otherwise.

Let it be a television show, for cripe’s sake.

I’ve said from the beginning that the easiest defense of The Chosen is that it’s a good show. It’s well made, the art direction is good, the performances are good, and there’s some genuinely creative and moving depictions of events from the Gospels.

I think this kind of response is exactly the attitude that reasonable people would want to cultivate in their audience. I also understand that fandom is crazy and that people who likes something really get into it.

But the audience of the show needs permission, from public-facing representatives of the show, to treat the show like it’s a show. It’s not a movement. It’s not always right. People should be encouraged to do their own fact-checking (Jenkins does encourage people to read the Gospels at least, which is a good start). And, people should be encouraged to challenge the theology and not always agree. If the show insists that charitable viewers who are Christians will see their theology in the show, though, this becomes an unrealistic imposition that discourages discussion.

Arguing about whether people like a choice on a show is a normal way for fans to engage with it. But I can’t help but feel that, particularly in the fallout after Episode 4.3., that Jenkisn really wants to have the last word – the amount of media produced justifying this decision is by now longer than the episode itself. Jenkins is welcome to personally like the choice. He can think it is theologically meaningful. But it’s also fine for people who like the show to disagree with him. They don’t need to be talked into it.

I think including the roundtables is a good idea. A cursory review of fan pages makes it very clear that a lot of fans of The Chosen don’t know their Gospels terribly well and having some resources to clarify what was added and what isn’t is a good idea. But as I said, I think they can be improved, and the historical review process can probably be improved as well.

So I guess we’ll see in Season Five!

I'm glad you mentioned the emphasis on "individual faith in Christ" and "spiritual liberation from sin" over any sense of physical liberation or salvation in the show. Obviously I've enjoyed the way it has depicted the very real bafflement of the disciples between their expectation of a victorious military leader and the reality of his humble and otherworldly kingdom. But it did get under my skin a little during the Luke 4:16 sequence, when Jesus read from Isaiah about the "year of the lord's favor" in Nazareth and immediately took all the language about captives/poor/destitute and made it pretty much completely about spirituality poverty. Another thing I'd really love to see you look into here is how exactly church tradition is playing into the "flash-forward" sequences we've seen in the show. In season 4, we've got Mary living in a cave and the mention that Little James was impaled with a spear near lower Egypt. I don't mind that kind of stuff being imagined from scratch, but it's definitely not in scripture—and I tried to find some evidence of historical tradition mentioning this manner/place of death for James The Lesser, but came up short. So I've wondered what exactly is going on there. It feels like the kind of thing most viewers will watch and go, "huh, well, there must be some historical basis for this speculation" and I can't tell if there is.

I am shocked to learn that this show only has three consultants, but the fact that they are sometimes commonly ignored and that a lot of the theology of the show comes from Jenkins isn't surprising.