The Horrible True Story that Inspired Sound of Freedom is Probably Our Fault, Part 2

Who took kids from Haiti? Why did they do it?

In the last section (please read that first), we talked about the horrible true story of Gardy, which inspired the character and story of Rocio in the movie Sound of Freedom. In the true story, Gardy was kidnapped in 2009 by a family friend, shortly before the 2010 Port-au-Prince earthquake. It appears he was left in an orphanage in the Martissant neighborhood of Port-au-Prince at an institution called Refuge des Orphelins. The proprietor and teacher, Yvrose, may have been involved in the original ransom scheme (she was the emergency contact information at the jail for Gardy’s kidnapper, Carlos). Refuge des Orphelins (which appears in the IBESR 2013 report on Haitian orphanages and, while not accredited, seems to have passed its last inspection), operated with a steady stream of Western donors and tourists. This is what critics of child institutionalization call “orphan tourism” – the process of programs turning a reliable profit not necessarily by selling children themselves, but selling voluntourists and missionaries the experience of interacting with orphans.

This to me seems to explain some of the apparent complications of Ballard’s report. For instance, Ballard reports that the orphanage was “hellacious,” and yet his footage looks pretty similar to photos that Yvrose herself took of the orphanage and shared on social media. Volunteers have said it was actually a well maintained facility. Ballard seems to have interpreted this experience as one of simple neglect since the orphanage was only a way-station for kids about to be sold. However, if the orphanage looked to be in bad shape, that can easily be explained for reasons other than trafficking. The need could obviously be genuine, or even part of attracting donations to maintain upkeep. Performing poverty and deprivation to a standard that will attract support is actually a key component of orphan tourism. Donations of lasting goods, like toys and shoes, are accepted from volunteers and then sold again because a well-equipped orphanage will not keep getting donors and volunteers. Orphanages depend on children appearing neglected (and actually being so) so that westerners will pay for the opportunity to help them. As long as Gardy was an institutionalized child, he was a commodity for the institution he was sold or not. Americans, Canadians, Australians, and Western Europeans were willing to pay for the opportunity of “taking care” of him.

Now, Yvrose actually was arrested for accepting payment in exchange for a child. There is footage of this occurring. According to Ballard, Yvrose provided him with instructions to take the child back to the United States without being stopped by the police.

In OUR literature, this is communicated as evidence that Yvrose was long in the habit of selling children for sexual exploitation. However, monstrous, systematic, well-heeled sex offenders weren’t the only people buying and selling children in Haiti in 2010. When Yvrose, and others like her, sold children – who exactly were they selling them to?

Chapter 6: Laura

On January 22, 2010, ten missionaries from Idaho arrived in the Dominican Republic in service of the New Life Children’s Refuge. They had previously bought property in the DR with the goal of establishing an orphanage there. Their goal was to establish a chain through the DR by which “loving Christian families” would be able to adopt children from Haiti. However, the Port-au-Prince earthquake inspired the missionaries to act before the permanent shelter in the DR was constructed. The group arrived by bus in Haiti on January 25, 2010. On January 26, the group was stopped while attempting to return to the DR with a group of 40 children, but they were stopped at the border by a police officer who told them they could not bring the children to the DR. On January 29, 2010, the group returned a second time with 33 children, including a three-month old baby, from the town of Callebasse and the neighborhood of Le Citron in Port-au-Prince. This time, the ten were arrested for kidnapping. The parents of the children later argued that they had been urged to hand their children over to the group in the wake of the earthquake, given the devastation of their homeland. The parents had been told that their children would be nearby and accessible; however, NLCR’s mission statement and action plan made it clear that they intended to bring the children back to the United States.

All 33 children were returned to their homes after the incident. They weren’t orphans.

The leader of this operation was Laura Silsby, who maintains that the children were orphaned or surrendered by distant relatives. Eight of the missionaries were later released. Laura Silsby, then aged 40, and her assistant and live-in nanny Charisa Coulter, remained held.

Laura insisted she had been given clearance to remove the children. The consul general for the Dominican Republic in Port-au-Prince, however, denied that Laura had proper documentation to take children out of Haiti. Eventually, charges of kidnapping and human trafficking against the women were dropped. Laura was sentenced to time served for “organizing illegal travel,” and released.

Haitian national Jean Sainvil defended the practice of the missionaries on the grounds that epidemics would arise in the wake of the destruction and the children needed to be taken away – parents were not able to care for their children in Le Citron even before the earthquake. Shani N. King, however, argues that this is evidence of how little the integrity of impoverished families is valued in Haiti, particularly by Westerners.

The story gets even grimmer upon the discovery that NLCR was collaborating with a man who would later be arrested for human trafficking and was wanted for presumed charges of sexual exploitation of migrants. The fact that the group collaborated with a known smuggler suggests that NLCS absolutely intended to sneak the children into the United States to place them with American families. All this suggests to me that the label of “human trafficking,” as distinct from poorly documented international adoption or “red-tape-skirting,’ low-accountability adoption, might not be as clear as we think. The UNICEF definition of child trafficking does include illicit adoption as a form of trafficking. Why wasn’t Laura Silsby seen as a human trafficker, but her advisor – a well-known human smuggler who provided her legal advice on how to get children out of Haiti without documentation – was? Is the difference only sexual exploitation? If so, how did NLCR intend to prevent this from befalling children in the US? Isn’t most sexual abuse in the US committed in families?

This story has attracted its own mythology in Q Anon networks due to the eventual involvement of then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and special envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton’s involvement in bringing Laura Silsby back to the US. Laura Silsby’s operation and even some emails from her show up in the Wikileaks emails from the hacking of Clinton’s email servers. Laura also had a pretty complicated history with shady business dealings and was facing significant financial misconduct allegations in Boise in 2009. Her home was repossessed only a month before she launched her trip to Haiti.

But the reality is, you don’t really need a conspiracy behind the conspiracy here. There is no further, darker reason why Americans would be eager to take children out of the United States. I don’t think any serious person thinks that Silsby’s stated mission of taking kids out of Haiti to bring them to the DR and eventually to the US was done so the Clintons could eat the kids. The motive of taking children to be raised by American families who wanted more children was enough.

In fact, while this particular incident was halted, and the children returned home, many, many more Americans actually did take children out of Haiti in the wake of the 2010 earthquake, with minimal documentation that the children were orphaned and needed to be adopted by new families. I don’t have any records of anyone else who employed a human smuggler to do this, as Laura Silsby did. If they did, I don’t think they’d exactly put it on their Facebooks.

Nonetheless, a lot of people did take kids out of Haiti, even if they knew their parents were alive, even if they could not confirm their parents were alive.

They were doing it to raise the kids.

And they did it in plain sight.

Chapter 7: The 2010 Special Humanitarian Parole Program

Following the 2010 earthquake, international adoption agencies were overwhelmed with requests from Americans who were eager to adopt babies, or had already been looking to adopt and wanted to adopt others. The Obama administration sought to expedite adoptions that were already in progress. If a Haitian child was in an orphanage without water, food, or power, instead of allowing them to languish in the hospital the child should be taken to the U.S. and the paperwork would be arranged in the US. This was called the Special Humanitarian Parole Program. Evidentiary standards that an adoption was “in progress” was incredibly low. Basically, if an American had demonstrated interest in adopting a specific child, this child could be taken to the US and the process would be continued there.

The reality is that the adoption process became chaotic as children were removed from Haiti for foreign adoption without evidence that they actually were orphans or had been surrendered by a blood relative. Children were adopted with no paperwork, incomplete paperwork, Haitian orphanages that were not licensed to carry out adoptions and were not damaged by the earthquake still were cleared out as children were airlifted out of the country in droves for international adoption. The Bresma Orphanage was cleared out despite the fact that many children in the orphanage had no prospective parents and were put into foster care in the Pittsburgh area. Towards this end, prospective adopted parents used political connections, moneyed megachurches, and even private planes to get children out of Haiti and into the United States. In the midst of this, many children were taken from Haiti with no documentation – or, in the case of Beechestore and Rosecarline Stroot, over the protests of their living father who did not want the children to be adopted.

On April 14, 2010, at the urging of the Haitian government, the Special Humanitarian Parole Program was ended.

According to the NYT, Owen and Emersyn McKee, each age 3, arrived in the US with minimal documentation and only their adopted parents’ word for it that they were orphans in need of a home.

Is it that crazy to suppose that maybe Owen and Emersyn (which I strongly suspect were not their given names) weren’t orphans? Or that a system that allowed a Haitian 3-year-old with no documents to become Emersyn McKee in Pennsylvania could have done the same thing to abducted children like Gardy?

When Yvrose told Tim Ballard that for $10,000 she could help him get a child into the US, is this what she meant? Orphanages like Yvrose’s did send children to the United States, and children with Gardy’s level of documentation (namely, none) did arrive here.

I want to return to a sentiment we named in the last article that I have seen expressed around OUR material and the movie Sound of Freedom. The line between good and evil is never as clear as it is around human trafficking. There are evil people who traffic kids, and good people who rescue them.

Is it? Is the line this clear?

We’ve already discussed how surrendering a child to an orphanage with the understanding that this is a temporary arrangement is a common practice in Haiti. It’s also similar to the cultural practice of wealthy Haitian families hosting restaveks (from the French rester-avec, “remain with”), or children who will be fed and educated in exchange for domestic labor. In the case of orphanages, the surrendered children are profitable, because of their use as commodities in orphan tourism. Was the line clear for parents who gave their child to orphanages, only to realize their children were no longer their own? Was the line clear for the endless stream of donors and missionaries who kept the orphan trade alive? Was the line clear for the parents who took children – who had no idea if their children had living parents or even ignored clear evidence that they did – to be raised as their own in the United States?

I’m not denying these people love their adopted kids. I’m not denying their intentions, or the legitimacy of their families. I have two cousins who are intentionally adopted, and the subject of international adoption – particularly transracial adoption – is about as fraught as a conversation can be. Likewise, I am not trying to glibly criticize the process of bringing kids to the US quickly in the wake of the Port-au-Prince earthquake. In the absence of food, water, and sanitation, some children almost certainly lived in the US who wouldn’t have lived in Haiti. I am just acknowledging what happened in this case, and how many ethical lines in a harrowing situation, in the midst of extreme family instability were either muddled or crossed. Are these lines clear?

The story of Gardy in the movie Sound of Freedom was repackaged to be a story with clear lines. American Christians, the good guys, fight (or donate to the fight) against child trafficking, which is done by others, the bad guys.

We don’t know where the story of Gardy himself ended. But the story of the people who took kids like him is not a contest between good and evil. It’s an intramural sport, and the story is older than the Haitian earthquake. American Christians supported the industry that took them – orphanages. American Christians supported the industry that removed them – adoption. And then American Christians fought those systems. Americans in Haiti were not just fighting the traffickers, and supporting the traffickers financially. They also were just doing the trafficking.

Who took Gardy? We took Gardy.

Chapter 8: Where’s Gardy?

Who took Gardy? And why did they do it?

This is the place of the story where I have to be incredibly careful what claims I am making. I am not claiming any specific insight into this case – in fact, in 2018 Ballard claims that he got a tip that Carlo’s brother Wilson may have been involved in the kidnapping. Wilson was arrested, though again, further details about whether he was tried or convicted are impossible to find. Guesno Mardy, Gardy’s father, knows far more about this case than I do, and has far more investment in it than I do. I am keenly aware of the optics of a 30-something white woman trying to solve crimes on the Internet with only the power of Google. I’m not trying to act like I solved this case. I don’t know what happened to Gardy himself. I am only trying to sketch the broad outlines of the system in which Ballard and Guesno seem to believe Gardy was swallowed up by – the orphanage system and its surrounding industries.

In light of all this I have some questions that, to the best of my knowledge, Ballard has never publicly raised.

Who was taking Haitian toddlers out of Haiti in 2010? Was it sex traffickers? Sugar cane plantation owners? These were groups that were publicly named as possible child thieves in the wake of the earthquake. Girls in particular were vulnerable to exploitation as domestic workers and forced sex workers after the 2010 earthquake. Other children were trafficked into begging and agricultural labor. Some Haitian officials mentioned fears of organ theft, but I’ve struggled to find documented evidence of this and the ADL seems to have labeled this as a variety of the antisemitic blood libel conspiracy. Gardy was a boy under three, and if he was sold in early 2010 (if Yvrose had him in the summer of 2010, he’s not in any photographs of her facility, which was extensively documented by American tourists). I haven’t been able to find documentation of three-year-olds sold for agricultural labor – not because of ethics, I assume, but because of economics. I’m not denying it happened. I’m strenuously praying it didn’t.

There’s only one group I can find extensive evidence of taking children under four (particularly boys), without any paperwork, out of Haiti. And those are Americans looking to adopt.

This fits with documentation I can find elsewhere about child trafficking in the developing world. In China and Eastern Europe, most babies and toddlers who have been stolen and sold were sold for the purposes of international adoption. Babies and toddlers are valuable because American families want them.

Is there any possibility, perhaps, that an American family took Gardy?

The painful truth is that, based on publicly available information, Gardy may not have survived the earthquake or the subsequent cholera outbreaks. Evidence is also incredibly sparse that he even made it to Yvrose’s orphanage, or that Yvrose knew anything about him. But Yvrose’s orphanage is illustrative of the dangers facing young children in 2010 in Haiti. Though Refuge des Orphelins remained standing in 2010, it did not have reliable access to clean water. Yvrose reported a cholera outbreak to the Redwood association in 2012, but I could not find clarification on when exactly this happened. Almost anything could have happened to him between 2009 and 2014. (As I said, he’s not in Yvrose’s photos in 2010-11. Believe me, I looked, and I expect Guesno did too).

But if he survived, it seems that a possibility that Ballard has at least never discussed publicly is this: Gardy was sold, not to traffickers who wanted to exploit him, but to Americans who wanted to raise him. He was sold to people who wanted to adopt without the red tape, he lives in America to this day, and, taken from his home as a toddler in 2009, he has no idea who he is.

I have no solid evidence that this is true. However, everything I have read about Gardy’s story, and the involvement of Americans in Haiti in the wake of the Port-au-Prince earthquake, suggests that this is a true, disturbing possibility. I have no idea if anyone has looked into this (I sincerely hope it has, given how plausible it seems), or if Yvrose has shared any information that I do not have.

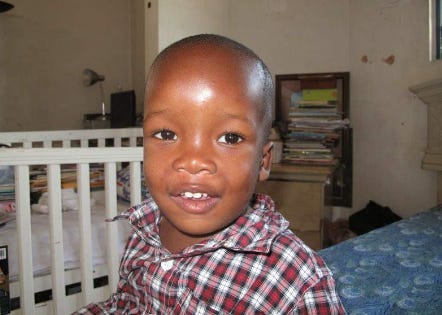

I suggest this with some trepidation, but if someone you know was adopted from Port-au-Prince in 2010: this is Gardy.

If you know this child, photographed in 2009, Gardy’s father is still looking for him. He always will be. His name is Guesno Mardy, and if there is a chance that we have his son, we owe him answers. Gardy would be sixteen years old now. If you have seen him, please reach out to OUR, which is still in contact with Guesno and still carrying out a search for Gardy. As I said, Guesno certainly has more information about this case than I do, and there may be information that Guesno has not made public that already eliminated the possibility that Gardy was sold to the United States as an adopted child. This may be in vain. But, with the publicly available information I have, it seems worth a try.

This series continues with part three.

All of this rings plausible to me, and is consistent with the fact that so many countries closed access to international adoption in the 2010s.

Nonetheless, you have poked a hornet's nest, and I hope the fallout doesn't get too intense for you.

Thanks for this. It's always hard to speak the unvarnished truth, and even harder to get others to see it. I hope this gets through to people.