No, Paul Won’t Teach Seminaries of the Future through the Miracle of AI

The farcical idea of bringing back dead thinkers for the classroom

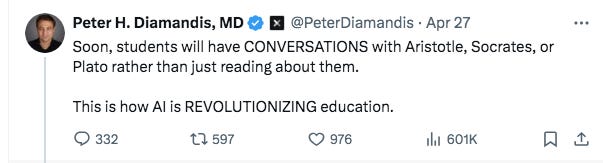

Okay. So, what dumb idea about AI are we looking at today?

In the future, we’ll be able to have students not read from historical figures, but actually talk to them. And not any historical figures!

The ones in the Bible.

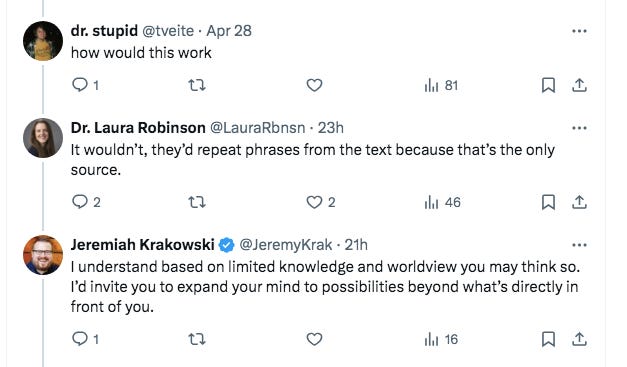

I thought we’d already settled the question of whether or not a language learning model could replace the presence of a dead person through one of Black Mirror’s few good episodes, but I guess I’m the idiot and if I open my mind I can understand that software can be basically as good as Paul.

So I tried to open my mind and think about it but you know what they say about open minds: you can’t open your mind so much that it falls out. Open mindedness about technology cannot solve the very basic historical problems that prevent us from recreating the actual mind of a historical figure based on literary sources.

This is where I expect to often just be flat-out disagreed with by some kind of vague appeal to “in the future,” but the problem is not that I can’t imagine really good technology. Ready Player One could happen tomorrow and we still wouldn’t have more sources from historical figures that would help us reliably reconstruct what they would say in a range of contemporary situations. This isn’t a tech problem, this is a history problem. We can’t remake figures from the Bible with technology, and there are very good historical reasons why.

For argument’s sake I’m going to focus on Paul, because I think he’s the strongest case for a re-creatable historical voice from the Bible. He’s one of the few figures about whom we have first hand information and something approximating direct language (a fact that I strongly suspect enthusiast do not know, but whatever). And even then, the problems of recreating Paul are insurmountable.

If I have misunderstood the tech at any point, I’m happy to hear corrections because I’m not a software engineer. But I don’t think you have to know a lot about the software itself to see the problems – can you predict what one person 2000 years ago would say in a range of situations now, based on 7-13 letters covering a limited range of ancient subjects?

Problem One: There’s No Unmediated Paul and Not Much First Hand Paul

According to scholarly consensus, there are between seven to ten authentic letters of Paul in the text of the New Testament. The Dutch Radical set (which is fringe but does exist) argued for fewer, and some scholars like Luke Timothy Johnson made the case that the pastoral epistles are authentic. As far as first hand Paul goes, this is all we have. At the very best, we have thirteen letters from him, but if you want to play it safe when programming a language model it’s probably fewer. That’s not very much material (And it’s better than the data set for virtually any other figure in the Bible). For comparison, Open AI’s GPT-3 model learned from about 570 GB of texts. That’s about one million books of 100,000 words each – so many, MANY times more than the amount of words necessary.

These letters, I need to emphasize, are still not unmediated access to “how Paul talked.” The letters had to be collected and compiled. They may well have been edited. They were almost certainly written with the help of scribes, except for parts of Galatians where Paul explicitly says he is writing himself (Gal 6:11). This is the closest we can get to Paul, but it’s still not Paul. Even the Corinthians thought there was a pretty big difference between Paul’s letters and Paul himself (2 Cor 10:10).

So what else is there? Well, there’s Acts, which contains an extensive biography of Paul. But this is, of course, explicitly second hand access to how Paul talked. We can use it to fill out the field, but we’re filling it out with Paul as Luke wrote him. Composing or collating speeches for the purpose of filling out a bios was part of literary practice in the ancient world, and Luke probably did alter direct speech from his sources to fit the literary needs of his own work. So if we add on Acts, we’re not really adding Paul, per se. We’re adding Luke’s Paul. We could also consider adding other acta like Paul and Thecla, but as we go the link between the historical Paul and the words ascribed to him only grows murkier and murkier. In reality, there’s just not that many words of Paul. You’d have to use a larger data set and texts that have minimal, if any, plausible relation to Paul.

It’s not inherently wrong to try to teach a computer to sound like Paul using words that aren’t from Paul. Paul presumably said things all the time that aren’t in his letters, like “I’m going to bed,” or “hand me that awl.” He probably talked to and made jokes with friends in a conversational tone and used speech patterns that were generally common to the population on the whole. Paul did not speak in a completely sui generis way, he spoke in a way that was intelligible to and similar to other people around him.

But that doesn’t mean we can get a computer to speak to Paul using any language whatsoever. For one thing, Paul didn’t speak in English. He spoke Greek – specifically, Koine. We don’t have tons and tons of records of what Koine conversations sounded like. We have some texts in Koine, like Polybius, Plutarch, and other texts of the New Testament. We have Marcus Aurelius’s private writings. We have papyrological and inscriptional evidence. And we have texts that have been translated into Greek, like the Septuagint. But we don’t have conversations in Koine that can give us an idea of what conversational Koine might have sounded like. And within that, we don’t have any specific understanding of how Paul might have talked. He presumably didn’t sound like his letters – I doubt he talked for sixteen chapters at a time. The possibility of whether we could get a software program to “talk” like a native Koine speaker at all is inherently unlikely. Approximating one particular Koine speaker is even less likely.

So as far as reconstructing Paul goes, it looks to me what we have is basically the part in Jurassic Park when the scientists harvest dinosaur DNA from amber but have to fill in the “holes” in the sequence. In the book and movie, the scientists solve this issue by filling in the gaps with frog DNA. It works perfectly and there are no further difficulties. So thinking along the same lines: if we were going to fill in the “holes” in Paul’s language with other sources, and we can’t use conversational Koine, what can we use?

Well, I can tell you what Chat GPT Uses: English idioms and the rest of the Bible.

Problem Two: Frog DNA, or “How Are Those T-Rexes Having Sex With Each Other?”

So let’s look at how ChatGPT 3 solved this problem. I know there will be some hand-waving about how this is just the beginning and later models will be much better but 1) based on part 1, I can’t see how that’s possible and 2) this is still pretty illustrative.

The primary problem AI language generators have to solve with creating the speech of an ancient figure is the lack of access to the language that person used. This problem cannot be solved with better software. The problem is a lack of source material available with which to train the software. We have to fill it in with something – the “frog DNA” from Jurassic Park, so to speak. So the way ChatGPT solves this problem is 1) direct English language translations from Paul and 2) quotes from other parts of the Bible.

This is what ChatGPT gave me when I asked it to write me a Pauline epistle:

To the beloved brethren in [insert destination],

Grace and peace to you from our Lord Jesus Christ, who gave Himself for our sins to rescue us from the present evil age, according to the will of our God and Father, to whom be the glory forever and ever. Amen.

My dear brothers and sisters, I write to you with a heart filled with gratitude and love, for I have heard of your faithfulness and perseverance in the face of trials. Your steadfastness in Christ is a testament to the power of the Gospel working within you.

Yet, let us not grow weary in doing good, for in due season we will reap if we do not give up (Gal 6:9). Remember always the words of our Lord, who said, "In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world."

Let love be genuine. Abhor what is evil; hold fast to what is good. Be devoted to one another in brotherly love. Honor one another above yourselves. Do not be slothful in zeal, but fervent in spirit, serving the Lord. Rejoice in hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer (Rom 12:9-12 ESV).

For we are all members of one body, and each of us has a part to play. Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. Let us use our gifts for the edification of the body, that we may build one another up in love (1 Cor 12:12-14, sort of).

Let us not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of our minds. Let us set our minds on things above, not on earthly things, for our citizenship is in heaven, from which we await a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ (Rom 12:2).

And let us not forget the words of our Lord, who said, "By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another." Let love be the mark of our identity as followers of Christ, for love covers over a multitude of sins.

May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all.

In Christ's love,

Paul the Apostle

Okay, so what do we have here?

The opening is vaguely reminiscent of a phrase in 2 Thessalonians, but let’s not ignore the fact that it’s not the way any Pauline epistle starts.

The first paragraph is basically just Galatians. The second paragraph is recognizably non-Pauline in its vocabulary. “Perseverance” actually sounds more like James than Paul. “Testament” is not really a Pauline word at all. He generally favors the word “witness.” “Trials” are a major theme in James and 1&2 Peter, not as much in Paul. Paul uses the word πειρασμὸς in 1 Cor 10:13, but that’s it. It’s also interesting that ChatGPT goes for a gender neutral translation of ἀδελφός, which isn’t wrong but definitely more of a modernism.

The third paragraph is, again, just Galatians.

The fourth paragraph is a hash of the 1 Cor 12 image of “one body from many parts.” The body in question is never equated to the church, just Jesus, and the metaphor suggests that just as Jesus is literally made of many parts, so are we.

Finally, Paul plays us out by quoting John a second time and then repeating a phrase from 1 Peter. He then signs his letter “The Apostle.”

So what do we see here? The big thing I’m noticing is that, unsurprisingly, the small amount of Pauline material makes it very difficult to produce original material that actually sounds like Paul. So ChatGPT has solved this problem by (what looks to me) drawing on Paul’s speeches in Acts. Paul doesn’t really quote Jesus in his letters, but he does in one of his speeches in Acts, when he tells the Ephesian elders to remember a quote from Jesus that is otherwise unattested in the New Testament (Acts 20:25). AI Paul goes ham quoting from the Gospel of John that was almost certainly written after Paul was already dead. So this is a more Lukan Paul than an epistolary Paul, and also Paul who has a heavy bent towards a Gospel that otherwise has very few theological and literary links with his own message.

When there is original content it’s jarring how much it does not sound like the translatd letters of Paul. Some of these phrases just don’t sound like translated Greek at all – for instance, “a heart full of gratitude.” A heart is actually never said to be “filled” in the entire New Testament, and I can’t find any equivalent phrase in the Hebrew Bible either. The idea of a heart being a container that is filled with emotions just is not a semitic idiom, and people like Paul didn’t use it. Hearts can be lifted up, or poured out, and one’s heart can feel things (Rom 9:2). But it is not “full” of feelings. Even if we argued that Paul, if we taught him English, might say things like this, we still don’t know that Paul himself would have used this phrase. “I write to you with a heart full of gratitude” isn’t such a common American idiom that it would be unsurprising if Paul used it regularly. It’s pretty florid language that makes Paul sound like he’s giving a wedding toast. It might characterize how Paul would sound to his contemporaries, but it also definitely might not.

Or consider the phrase “a part to play,” which has been inserted into Paul’s Corinthian correspondence quote. This is metaphorical language drawn from the world of theater – to “play a part” means to (metaphorically) perform the role for which you were cast. But the New Testament doesn’t use imagery drawn from the field of drama. If Paul saw plays he doesn’t talk about them. Tertullian even argued that Christians shouldn’t go to the theater at all. As always, this suggests that some early Christians almost certainly did go, but this isn’t a well-attested metaphor field for early Christian writing.

But honestly, what else could the software have said that wouldn’t have this problem? Either you draw directly on Paul, or you say something novel that invites the immovable question of “would Paul have said that?” Perhaps ChatGPT Paul could have used a metaphor from cooking, or from weaving. We’d still be left with the question that we can’t answer with the tools of history: “would Paul have known how to cook that? How much did Paul know about weaving? Would he have said that?” Or, if the software was completely contemporary in its style and had Paul make a Sopranos reference, “Would Paul have watched The Sopranos? Would he have liked it? How would he have engaged with the materia?” These aren’t questions that we can answer with the tools of history, but they remind us again and again of the central problem whenever a generative tool imitating Paul says something Paul didn’t actually say: it’s not Paul, and the question of whether or not Paul would have said something like this is either contested or unanswerable with the tools of history.

Just like the frog DNA in Jurassic Park turned the cloned dinosaurs into something that’s not a dinosaur – namely, a dinosaur that can change its sex for the purposes of mating – additional sources besides Paul makes ChatGPT Paul into something that’s not Paul. It’s Paul plus an imaginative recreations of what Paul might be like. If we take that part out, we just have the letters, and ChatGPT is not necessary for an encounter with Paul. If we add it in, we’re not engaging with Paul anymore.

In light of this, it would not be appropriate for a teacher to assign students to engage with an AI recreation of Paul and treat the answers as though they were authoritative about what Paul would actually say. They are not. You could do a fun classroom exercise where you compare AI Paul to Letter Paul and argue in an essay format if Letter Paul would agree with AI Paul. But you can’t treat them as the same. They’re not the same.

Problem Three: Paul in History Didn’t Act Like Software

The idea of being able to speak to a figure from the Bible through AI is presumably to be able to get clarification about what he meant when he said certain things (as we’ve already said, not possible) and to ask that figure to speak into a present-day situation. For example: a teacher would be able to pull up PaulGPT, ask Paul what he thinks about the pro-Palestine demonstrations on college campuses, and Paul himself would answer.

The fact that anyone would think this is a thing Paul could or would do reveals the extent to which they do not understand Paul as a thinker at all.

Paul’s letters are not generalizable dictates written in the style of a theological textbook. They are contingent. They are written to people he knows, or who are closely associated with people he knows, from the context of a relationship. Paul did not just write letters, he wrote them to people and situations.

So if we were going to ask Paul to speak about a contemporary issue, even if we were in a science fiction movie and brought the real Paul to the present so we could ask him our questions, the amount of time we’d first have to spend catching Paul up on everything he’s missed would vastly outweigh the time he spent giving us instructions, because that’s how the real Paul worked. Paul received envoys from other places, got their news, and wrote back to those specific situations.

Think of all the things Paul missed that would be relevant context. Paul, when he died, did not know that several people wrote lives of Jesus that purported to record his actual words and deeds. He did not know that multiple strands of Christianity rose up across the empire, some of which had their own scriptures, competed over the meaning of his letters and eventually the proto-orthodox movement claimed his writings for their own. He didn’t know that following a period of empire-wide systematic persecution, Christianity was made licit by an actual emperor and eventually became the religion of the entire empire. He didn’t know that the letters he wrote would eventually become foundational to justifying Christian persecution of his own ethnicity. Paul didn’t know about missionaries taking part in expansionist powers in the Americas. He didn’t know about the Protestant Reformation, which was largely argued over the interpretation of things Paul wrote. He didn’t know about the doctrine of original sin. He didn’t know about the particular forms American Christianity would take. He didn’t know that the Jews were expelled from Jerusalem in 132 CE, that large portions of the Diaspora were settled in Europe, that there was a massive systematic campaign to wipe them out in the 1940s, and that after that many European Jews not only resettled Israel but established another nation there, but that in the meantime there was a mosque built on the Temple Mount so Jerusalem looks a little different now (by the way, we’ll need to catch him up about Muhammed) and anyways there’s a thing called universities now and –

Do you see what I mean by all this? Imagine catching Paul up on everything that happened with him, Christians, and Jews since 60 CE. Imagine telling him everything that happened. What makes you think the real Paul would even want to talk about any contemporary issue, once you explained that all to him? Once you’d explained all that to him, do you think any of his beliefs would have changed?

Paul, as he was, did not have that information, and that’s part of why Paul believed and taught as he did. Once you gave it to him, he would not be the same Paul. But a virtual Paul who does not sound like the same Paul from his letters would not be recognizable to us as authentically Paul. And a Paul who did have that information would sound very different from the Paul in the letters. But without a real Paul to compare it to, we cannot have any idea that this is what a (for lack of a better word) real time-traveling Paul would think. A student could not be led to believe that anything that emerged from such a program was “Paul” on the same level the epistles are. Even the letters themselves cannot provide unmediated access to Paul, but a predictive program — which would have none of Paul’s pastoral sensibilities or sense of being a person in history — definitely can’t.

Conclusion, and Comparison

All over the internet, right now, you can find blog posts and videos and clips from people who claim to speak in the prophetic voice for Jesus, or Mary, or other figures from the New Testament. (Seriously, look up “charismatic Catholics” or “New Apostolic Reformation,” it’s everywhere).

Would you bring such a person into a history classroom and have them speak for Jesus to the students?

I think the answer is pretty obviously “no, of course not.” And yet, it is hard to make the case that a charismatic preacher who speaks in the voice of Jesus could be outclassed by an AI Jesus.

The source materials are more or less the same — basically, deep learning of the words of a figure as mediated by historical writers. It’s also usually filled in by other texts from the Bible, as we saw with the ChatGPT example. And that person can easily respond to any question a student might have and give a predictive answer. Should a professor treat that person like Jesus for historical reasons?

No, we’d say that person is a kook and they’re obviously giving their own interpretation mixed in with the language of Jesus from the Gospels. It’s not Jesus, it’s a guy pretending to be Jesus. So why is a software pretending to be Paul supposed to be the real Paul? Or software pretending to be Socrates?

Realistically, I don’t think there’s a difference except that there’s something about technology that feels like itself a legitimizing force. “A person can’t speak for Paul, but a disinterested computer certainly can.” Of course, this ignores the fact that data sets and software are made by humans, and are themselves interpretive choices.

The invocation of technology obscures the fact that this is, at its core, magical thinking. It would be fun for the real Paul to come to class, and we’d learn a lot. But Paul is dead, and he can’t, and nothing is going to bring Paul back. Any Paul that shows up in your class is going to be a mutant Paul with the blank spaces filled in, and the person who filled in those spaces was not Paul but some other person. This is not meaningfully different from prophecy. This is not meaningfully different from having a medium. For the purposes of a classroom, Paul cannot be accessed outsized of history with non-historical tools. Anything else is neo-pseudepigrapha. Pseudepigrapha can, and was, sometimes done from apparently upstanding motives. But the results is the same. It is a forgery. And it should not be treated as authentic in an academic setting.

Well said. The concept of using AI to talk to historical figures seems to be based on the idea that because it's a *computer*, it magically has access to Truth in a way that people don't. Which is just not how AI works at all- ChatGPT is designed to produce something that sounds like something that someone would say, that's it, not necessarily something that is meaningful/correct.

But Laura, a MAN on TWITTER told you to open your mind because *gestures vaguely in the direction of AI*